A middle-aged white woman stands in a bunker.

She’s looking at a button.

If she presses that button, it will save the world…she thinks. But first, thousands will die–in pain and terror–and never know why. A dead-eyed military attaché indifferently counts down the seconds she has left to choose. Her chosen general, bristling with righteous anger, demands that she take the next step in the operation his men have already died for. And her daughter–the next generation–begs her tearfully to stop, pull back, reconsider.

She pushes the button. Seconds later, a Third World town is reduced to ash and dust.

A parable about imperialism? Drone warfare? The exploitation of the Global South in service of high-minded yet ill-defined goals? It is all of these, and it is also almost exactly the midpoint of GODZILLA: KING OF THE MONSTERS (2019).

GKOTM gets a lot of flak for some bad one-liners and questionable references. But when we step back and look at the whole picture, it’s intensely aware of the journey that Godzilla and other kaiju took from the ‘50s to the ‘70s from being the embodiments of environmental destruction to the avengers of the despoiled Earth. The “MonsterVerse” Godzilla is the Godzilla of Yoshimitsu Banno: director of GODZILLA VS. HEDORAH (1971) and producer of GODZILLA (2014) and GKOTM, and one of the two people to whom the latter film is dedicated.

But it’s been 80 years since SILENT SPRING, the book that inspired HEDORAH and kicked off so many environmental movements. The threat of today is climate change–the inevitable result of our oligarchy’s short-sightedness–and the ways our society will react to that change. GKOTM looks not to retread the same ground as HEDORAH, but to look forward at the threats of the future. As our environment deteriorates, as with all great disruptions, the worst of humanity will assert itself.

Enter Alan Jonah. Played by Charles Dance, known for depicting some of the most reviled screen villains of our time, he comes onstage with a massacre followed by a cold-blooded execution. We’ve never seen a moment like this in a Godzilla film before, and it reinvents the stakes. We soon learn that Jonah is an eco-terrorist; an accelerationist whose response to environmental loss is to burn everything down and build onto the ashes.

This stands in contrast to another early antagonist, Senator Williams. She represents the government, the orthodoxy. She sees the monsters’ rise as the cause of change, rather than the result of change, and her idea of a solution is to kill them all. A “nuke the hurricane” moment, if you will.

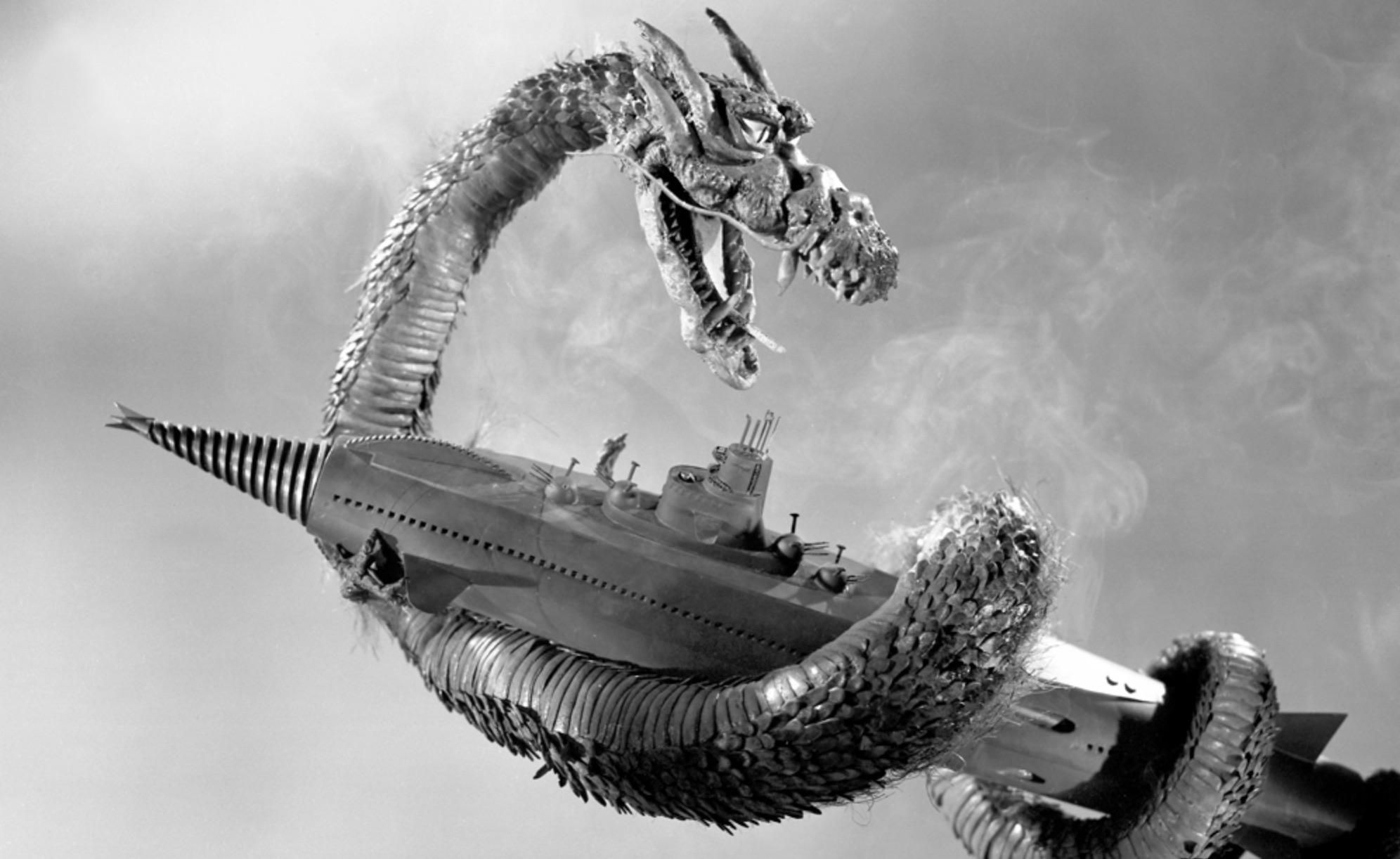

Monsters are always metaphors. Famously, in GODZILLA (1954), Godzilla was both the avatar of nuclear holocaust as well as its victim. His destruction was both necessary and tragic. We might observe that in GKOTM’s predecessor, GODZILLA (2014), it is the Mutos who play this avatar/victim role. Godzilla has graduated to the role of ecological avenger, much like Mothra in MOTHRA (1961) and himself in HEDORAH. In GKOTM, the monsters, including the Mutos, represent various different natural disasters that can follow in the wake of human rapacity. But the “alphas” Godzilla and Mothra also evoke a fictional–or perhaps mythic is the better term–anthropomorphization of the stabilizing forces present in nature. Like their Golden Age incarnations, Godzilla and Mothra represent the Earth’s capacity to repair itself from human insult, which is exactly why they are such vulnerable, mortal beings.

What Serizawa understands, as he defends himself from Williams, is that the monsters should not, and likely cannot, be stopped with simple force of arms. If we nuke the hurricane, we will either do nothing, or make it worse.

A shallow reading of the film might conclude that Serizawa’s response to Williams indicates that he is in broad agreement with Jonah, but this is not so. Williams disappears from the film; her fervent desire to defend the status quo is simply irrelevant in the face of the events that transpire. Serizawa accepts that the only way humanity can remain on the earth is to seek a peaceful accord with the great forces that exist within it, but Jonah just wants to nihilistically unleash those forces–and as we soon learn, Serizawa’s protégé Emma Russell now agrees.

Russell is given a substantial amount of screen time to explain her motives directly to the characters (and the audience) suggesting that they are of major importance to the filmmakers. According to Russell, by releasing the monsters all at once, the world’s decadent civilizations will be destroyed–Russell, her daughter, Jonah, and his troops all remaining safe in a bunker, a course of action she recommends to her former friends as well. Once the monsters have destroyed everything, their primal radiation will restore the “natural order” and the handpicked survivors will emerge into a new utopia.

In other words, Emma Russell is an eco-fascist.

Eco-fascists, like other reactionaries, divide all people into an in-group and an out-group. Anything that the in-group does at the expense of the out-group is permissible. In the real world, we are seeing the groundwork for eco-fascism get laid as the super-wealthy and politicians shore up borders and secure their enclaves. As climate change worsens and the refugee crisis intensifies, eco-fascists will appeal to safeguard what they think of as “civilization” by any means necessary. Conveniently, eco-fascists feel little need to restrain their consumption–why bother, after all? The faster the Earth deteriorates, the faster the undesirables will be killed off. This is why Russell is so comfortable with military force, and with taking actions that she absolutely knows will make things worse before they get better.

Most convenient of all, Russell’s hands are clean. She openly abhors the violence that Jonah wreaks at her own request. Did she really feel as if she killed the MONARCH scientists gunned down while she looked away? Or the no-doubt millions of victims of Monster Zero’s hurricane, or the inhabitants of (fictional) Isla de Mara? When you’re giving high-minded orders, or even pushing the button yourself, and killing from thousands of miles away, can you really understand what you’ve done? Russell’s moral descent teeters uncomfortably close to that of ostensibly liberal politicians and citizens who cheer on and benefit from the USA’s forever wars. (This is as good a time as any to note that GKOTM’s director, Michael Dougherty, is the son of a Vietnam War refugee.)

While Russell perhaps finds a modicum of spiritual redemption in the film, her damage is already done, because she has another of the great flaws we see in real-life schemers. One of the first monsters she releases is the one that she understands the least–Monster Zero. She didn’t know that Ghidorah is not one of the Earth’s ancient titans but an invader, with power enough to remake the world but no stake whatsoever in its survival. Setting aside its ghastly morality for a moment, one of the biggest problems with eco-fascism its refusal to acknowledge uncertainty. You can build palatial bunkers filled with well-paid security guards; you can blast particulates into the sky because someone did some math and figured yeah, that ought to cool the earth down; but you don’t actually know what’s going to happen. There are too many variables–billions of people, billions of species fighting to survive, billions of ways for the environment to change–for simple pie-in-the-sky plans to work. In the film, Russell’s ex-husband and former colleagues understand this and try to warn her off. “It’s not all math, Emma!” Appropriately, by the time Russell explicates her plan to them, her own arrogant, ignorant actions have doomed it already.

With GKOTM having taken firm stands against mindless status-quo ignorance and of murderous accelerationism, what pathway forward does it leave us? It’s perhaps best to acknowledge here that GKOTM is a work of escapist fiction, like many of its acclaimed predecessors in the genre. Somewhat notoriously, the film wraps up on a happy montage of Godzilla and the other monsters restoring peace and comfort to humanity. But there’s a reason for this too. If GKOTM is an eco-fable, then what’s the moral?

What Serizawa argues for, and dies for, is for humanity to withdraw its claim to dominion over the Earth. This ideology of domination, in the real world, lies at the heart of most justifications for abuse of our shared environment. God gave the world to us, so I’ll do whatever I want with it. But Godzilla symbolizes the way the Earth’s biosphere functioned before humanity began to alter it: the proverbial balance of nature. As the film’s action unfolds, humanity’s attempt to interfere with Godzilla with some new gadget nearly dooms the planet. The successful resolution only comes when we learn to fight alongside him and, in fact, let him take the lead.

In other words, maybe, just maybe, we can survive if we are willing to surrender our “crown” to Godzilla, and thereby renounce our self-proclaimed right to endlessly, ruthlessly exploit the Earth.

This is a levelheaded response. Thank you. I’ve seen bad-faith critiques of this film which ultimately boil down to media illiteracy like assuming that depicting = endorsement.

Have you seen C Animus’ videos on KOTM? They’re pretty good.

I haven’t, but thanks for the recommendation! KotM is top-tier for me, along with G54, GMK, and I guess now Minus One. 😀