The 1963 Toho Studios film Atragon is widely regarded as one of Ishiro Honda’s masterpieces. Written by frequent collaborator Shinichi Sekizawa, it depicts a fascinating scenario; a powerful remnant of Imperial Japan, having survived the Second World War, waits in the South Pacific to strike back against a world that has left them behind. In the end, they are persuaded to instead save that very world from a more fanciful, even older oceanic empire. While the film has Sekizawa’s trademark pulpiness and humor, it is unusually serious-minded, tonally closer to scripts by his peer Kaoru Mabuchi (Matango, Frankenstein vs. Baragon) than his earlier efforts on King Kong vs. Godzilla and Mothra.

Atragon breaks down into three very distinct acts. Act 1 is the most typical material for Sekizawa, focusing on a supernatural mystery–cars driving into the sea, men with burning-hot skin, sudden earthquakes–that two bumbling photographers stumble into in an effort to impress a pretty woman. That woman is revealed to be the adopted daughter of a former Imperial Navy admiral, who took her in after the presumed death of her father, the shipbuilder and submarine captain Jinguchi. The goings-on are revealed to be the work of sinister agents of Mu, an undersea empire, who try to kidnap them in order to draw out Jinguchi, who is not only alive but considered a major threat by the Mu.

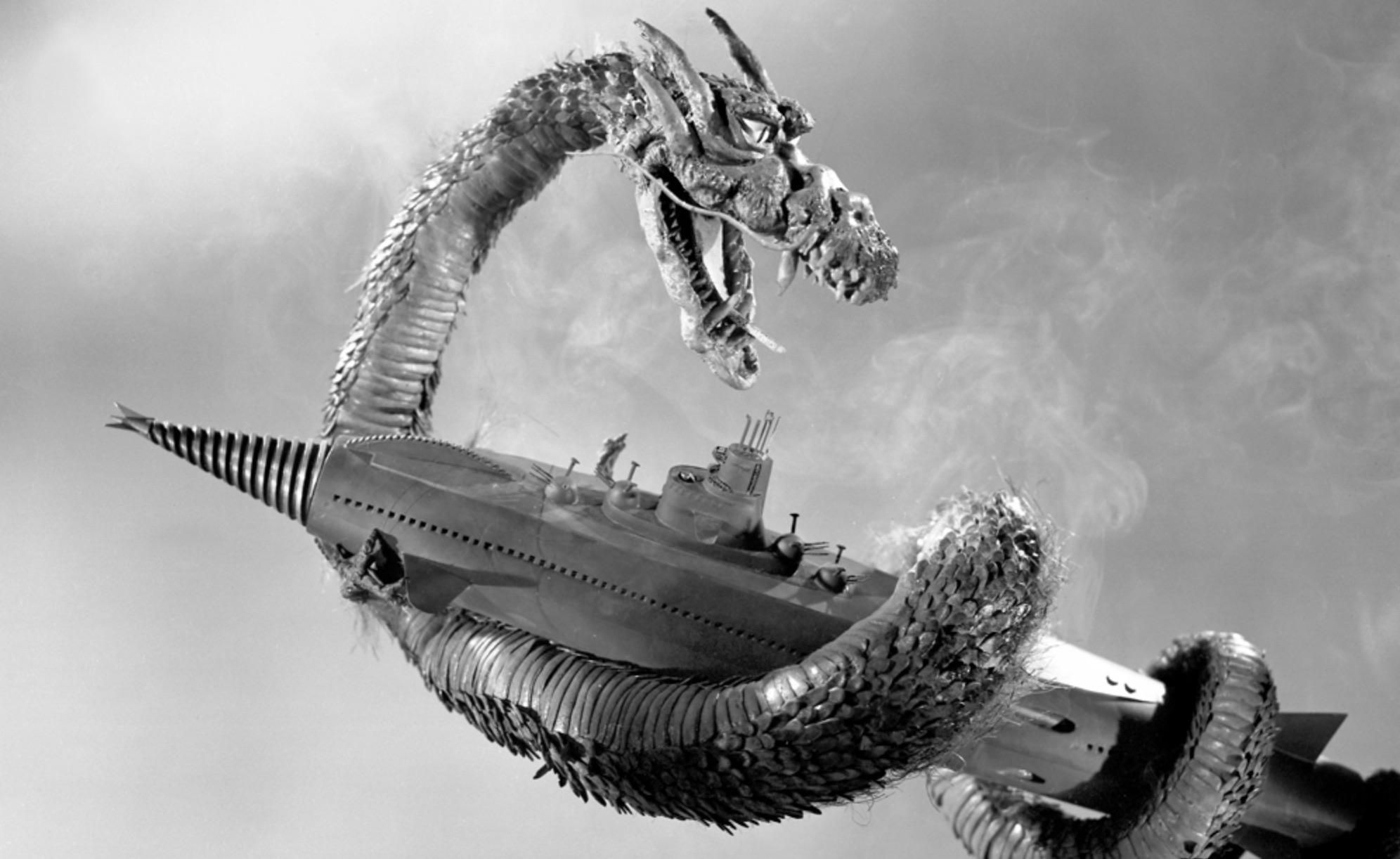

In Act 2, as the Mu use their high technology to strike at the surface world with impunity, the party from Japan seeks out and discovers Jinguchi’s island base. This is the most memorable and moving part of the film, as Jinguchi is still loyal to the now-defunct Empire of Japan. He has built a vessel, the Gotengo, that can do all the Mu fear and more, but it was Jinguchi’s intention to resume fighting the Second World War from this marvelous ship. Stoic to a fault, Jinguchi resists the emotional entreaties of his former superior and his estranged daughter, until at last one of the young photographers calls him a fool and “war crazy.” Before anything more can be said, Mu’s agents attack again, kidnapping the daughter and photographer and trying to cripple Gotengo. At Mu, far under the sea, the young pair discover a strange blend of the primitive and the futuristic, and are marked for sacrifice by the Mu Empress to the divine kaiju, Manda.

Act 3, in contrast to the others, is remarkably dialogue-light and action-heavy. The young captives not only escape but capture the Empress along with them. Gotengo swoops in at the nick of time to dispatch Manda and rescue them. Just as the Mu are stepping up their attacks on the surface, Jinguchi demands that the Empress order a cease-fire, but she refuses. Gotengo then drills into the Mu Empire’s power plant and plants bombs with a boarding party, causing the entire civilization to disappear in a massive fireball. Jinguchi then allows the Empress to commit suicide by jumping into the sea.

While the buildup of Act 1 into the masterful Act 2 ensures this film’s classic status, Act 3 has…issues. In light of the common enemy of Mu, the young Japanese characters, who had been harshly critical of the IJN holdouts, suddenly don uniforms and accept orders from Jinguchi. These ostensible heroes massacre squads of half-clothed spear-wielding guards using futuristic freeze-rays, and the resulting extinction of the Mu–implied to be millions of people–is not commented on. The most you can say of Jinguchi and his men is that they might be disturbed by the parallel between their fanaticism and the Mu Empire’s, but none of the hanging threads from Act 2 are actually resolved. Those of us who are familiar with the crimes of Imperial Japan may be left feeling unsatisfied by the resolution. In particular, we can contrast Atragon with the earlier The Mysterians, by Mabuchi, and the later Monster Zero, by Sekizawa, both of which explicitly have the defeated alien civilization survive and establish ongoing relations with the United Nations.

Why did Sekizawa get the script assignment for Atragon, rather than Mabuchi? This is speculative, but Mabuchi–a Communist–may not have relished an assignment that glorified Imperial Japan. At any rate, when Sekizawa–known for having a rather impish nature–returned to tonally lighter scripts, I believe he took some playful swipes at his own previous work.

The more obvious example of this is Godzilla vs. Megalon, which uses “Seatopia” as a lower-budget stand-in for the Mu. While the Mu are treated seriously in the Atragon text, they leave a bumbling impression in the visuals. In contrast, Seatopia is straightforwardly a society of blithering idiots. Their master plan is to mug an inventor to steal his robot in order to use as a guide for their own god-monster, who is too simple-minded to find his targets without it. In the lighthearted world of the late Godzilla series, these cardboard villains fit right in.

But the overlooked parody of Atragon is found in Ebirah, Horror of the Deep. This Jun Fukuda film, written by Sekizawa, is mostly a comedy of errors until the lead characters, shipwrecked on a mysterious island, unexpectedly encounter a dock and other signs of civilization. But the ship coming into that dock is unloading slaves, and its operators are the heavily-armed and uniformed “Red Bamboo” organization.

At first glance the Red Bamboo are very generic bad guys, but let’s break them down. While they do not wear IJN uniforms, their outfits are a similar style. There’s no indication that the officers and men are anything other than ethnic Japanese. There’s no mention of their politics, but what they are doing is essentially the same as what Jinguchi’s crew was doing–creating a weapon of mass destruction on an isolated Pacific island.

Much like the Gotengo’s crew, the Red Bamboo use indigenous workers–however, rather than employing local natives, the Red Bamboo kidnap them from Infant Island, previously seen in Mothra and Mothra vs. Godzilla. Rather than building the Gotengo with their island’s natural resources, they have built a nuclear reactor and are working on atomic bombs–certainly an appropriately ironic choice of weapon for Imperial Japanese holdouts. The organization’s leader is even played by Jun Tazaki, the same actor who played Jinguchi.

While the Gotengo crew are harsh, ruthless, and somewhat misguided, they ultimately proved forthright and competent. The Red Bamboo are cruel and irredeemable from their first appearance, machine-gunning unarmed prisoners and cackling as their tamed kaiju Ebirah slaughters others. Sekizawa’s narrative proceeds to happily cast them as fools–ignorant and totally unprepared for the threat of Godzilla sleeping on their own island, they lose their entire air force and their priceless reactor in a matter of minutes. Then, due to their complete failure to guard their own slaves, they are tricked into using a sabotaged batch of Ebirah-repellant and devoured by their own monster.

While the Red Bamboo’s appearance and modus operandi resemble the Gotengo crew, their downfall more resembles that of the Mu–they arrogantly rely on having superior technology, they are inflexible to changing circumstances, they’re obsessed with a kaiju ally that proves useless or worse, and they’re trivially outfoxed by their own prisoners. Yet this is no contradiction. An important element to Atragon’s thematic depth is its implicit comparison between the monomaniacal IJN captain Jinguchi and the obsessively aggrieved Mu. Perhaps those very parallels between the fictional Mu and the real Empire are what thematically required the Mu’s complete destruction in Atragon. Therefore, we can observe that the Red Bamboo in Ebirah, do in fact, synthesize the two parts of Sekizawa’s ultimate critique of Japanese imperialism.

Certainly in the early 1960s, the war and the occupation were very recent history, and many Japanese families must have at some point experienced the culture shock of the postwar generation in a similar manner as Jinguchi does. In that environment, the equivocation of Atragon regarding the legacy of Japan’s actions in WWII is understandable. The Godzilla series would ultimately have to wait for a new generation of filmmakers before it was ready to explicitly critique the violent excesses of Imperial Japan, with Shusuke Kaneko’s GMK in 2001.

I don’t know if Sekizawa was ultimately as unsatisfied as I am with the final act of Atragon, nor do I know if material in his later scripts was a reaction to this. In contrast to Mabuchi, he was not vocal about his politics. Certainly Ebirah director Jun Fukuda maintained later in life that he shot his Godzilla movies as a disinterested journeyman; it’s unlikely he would have knowingly tweaked the nose of an earlier Honda film. Yet Sekizawa’s scripts, even the “lesser” efforts like Gigan and Megalon, continue to capture our interest because of their playful self-awareness and their satirical pokes at contemporary Japanese culture. So I do believe that the stubbornness of Captain Jinguchi and the cruelty of the Red Bamboo both stem from Sekizawa’s own reckoning with the “war craziness” that had so recently afflicted Japan.