Photo by Dirk Skiba

One of the major landmark kaiju/tokusatsu adjacent releases of 2023 has been the debut of “Godzilla and Godzilla Raids Again” in wide availability for the first time in the United States. Previously these stories, authored by Shigeru Kayama, who is a well-respected Japanese science-fiction author, were officially unavailable. The best way to access these were to find a fan translation online, or simply, learn the language and try and hunt down the book on your trip to Japan. Kayama’s role in the genesis of history’s most iconic movie monster, as stated by Steve Ryfle, “went largely ignored by Western scholars”. Translator and authority on Japanese language, Dr. Jeffrey Angles, has set out to rectify this and put Kayama’s story out for western fans to see and educate themselves. Kaiju United has had the incredible opportunity to have a wonderful discussion and interview with Professor Angles to get his insight on Godzilla, Kayama’s thought processes, and the historical context behind some of the important moments found within Godzilla.

“Godzilla And Godzilla Raids Again” will be released on October 3, 2023, in major markets, and is published by University of Minnesota Press.

Special thanks to Heather Skinner.

Interview

JL: Jacob Lyngle (KU)

JA – jeffrey Angles

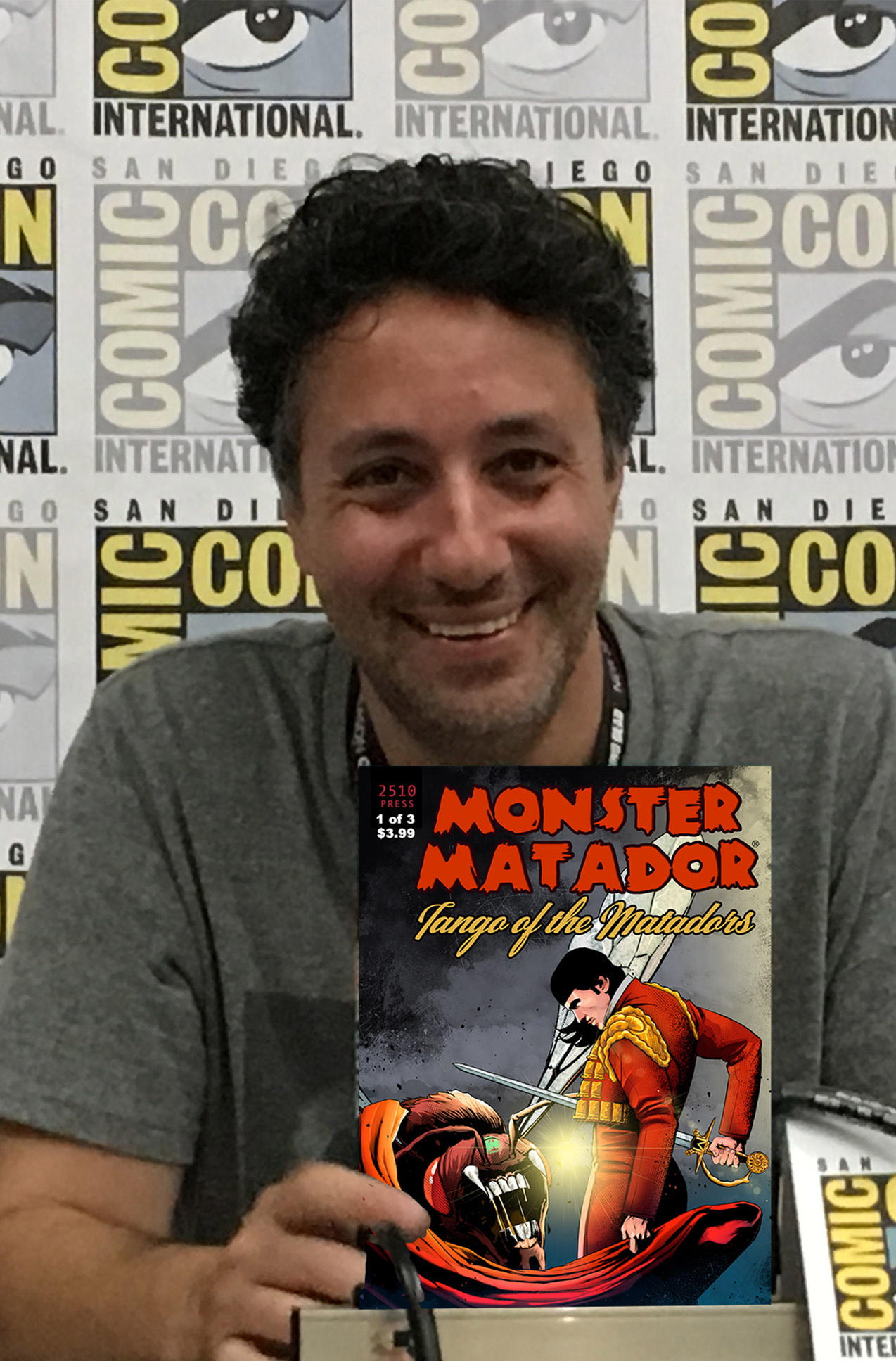

JL: Hello, Kaiju United! I’m here with Dr. Jeffrey Angles, who is a professor and advisor of Japanese language at Western Michigan University. He is also a translator and a poet in his own right. Jeffrey, do you want to introduce yourself? Anything I missed there?

JA: I think you got the main highlights! I work at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo. I spent most of my time working on Japanese poetry, but as a kaiju fan myself, I realized that these Godzilla novels had never had an official translation in the United Sates. I thought, this is something I must do. This is a new and exciting venture for me!

JL: It’s good to hear that you’re also a Kaiju fan because that was my initial icebreaker! I was curious to hear if you were a fan of the stuff before diving into Godzilla. Now, on the other hand, Nobuhiko Obayashi. You’re a big fan of his, according to some other podcasts you’ve been on. He’s best known for House (1977), but of his filmography, were there some others you are invested in or have been inspired by?

JA: That’s the one that’s made the biggest impression on me. There’s also a couple of them that haven’t been made available in the United States yet. There’s a spectacular one from the early 1980s about schoolboy and schoolgirl culture, which is fantastic. I don’t think it’s ever been released in the US.

JL: I don’t think it has. Was the English title “The Drifting Classroom“ by chance?

JA: There’s that one, but the one I was thinking of is School in the Crosshairs, which is about an evil warlock harassing a bunch of schoolchildren, including one who has supernatural powers. I thought its use of experimental film technique was incredibly clever and charming.

JA, CONT: In fact, I started out the early part of my career writing about a guy by the name of Edogawa Ranpo, a famous mystery writer who took his name from Edgar Allen Poe. Say it out loud and it makes sense—Edogawa Ranpo. (Laugh). That’s his name in the traditional Japanese order, with surname first. The wordplay doesn’t work if you put his name in the Western order. Anyway, he wrote lots of stories during the 1930s about weird creatures, dastardly villains, almost supernaturally brilliant detectives, and sorts of strange, erotic, grotesque things. I see Obayashi’s House and School in the Crosshairs as the modern inheritor of the same sensibilities forged before World War II by Ranpo and his generation. As I watch these films, the nerdy part of me is thinking about how they’re connected to what came before.

JL: Connective tissue is one of the best things you can put together when reading and studying media. I’m a movie guy myself. I love watching anything from around the world, and then just putting those pieces together. It just completely makes everything full circle. It’s so wonderful.

JA: I always think about literature and film as a lens into a specific moment in time. And that’s why this stuff is so exciting. I mean, of course it’s fun to watch Godzilla stomp on Tokyo, right? But it’s also interesting to think about why the film and the monster were created in the first place. Those sorts of considerations are hugely important.

JL: I’m going to go back to the beginning of your career a little bit. I know you went on a trip to Japan when you were young. And that’s kind of where it clicked with you, and you thought okay, Japanese is what I want to study. Was there something extremely specific you experienced while in Japan at a youthful age? There had to be something that made you go, okay, my whole life now is Japanese, and I am going to pursue the study of this specific language and culture, translate some work from there, and get a PhD in doing so. Any pivotal moments that shaped that decision?

JA: I fell in love with Japan partly because I had seen so few places when I was growing up in Ohio. I had been to the ocean briefly as a kid, but it was exciting to be sent to Shimonoseki, the southwestern Japanese small town that has the longest coastline of any city in Japan. There I was, overlooking the ocean, mountains behind me. And it was so beautiful and interesting that I knew right away that I really wanted to be able to understand Japanese and feel more at home there. I knew that I wanted to be able to access more than what I was just seeing on the surface.

JA, CONT: So, there wasn’t a single moment when I decided I’m going to dedicate my life to Japanese studies, but I decided early on that learning the language is important, because otherwise I’d only get a surface-level understanding. I’m sure many of your listeners and readers know that Japanese is a complex and hard language for native English speakers. It’s so completely unrelated to English in terms of its structure, its writing system, and so on. Many learners give up along the way. But, you know, there are wonderful benefits to be had by just hanging in there and slogging it through. Things just get more and more interesting. In Japan, I look around, and I realize how much of Japanese culture is not available to non-Japanese speakers. It makes me tremendously sad.

JL: It’s tragic. Our website [Kaiju United] focuses primarily on kaiju and tokusatsu adjacent media, and even just on that side, we’re just barely getting stuff carried over to the West now. The biggest one I can think of, Kamen Rider, just barely got a United States release, and it’s been around for what, fifty years?

JA: Yeah, yeah! Kamen Rider has been hugely popular in Japan for decades. It’s so big, there’re still reruns on Japanese TV. So, it’s crazy that popular media often takes so long time to arrive here in an official capacity. And I can say, in the scholarly world, there’re more and more people that are looking at popular things like Kamen Rider. There’s a critical consensus growing around popular culture, which, to me, is exciting. I love it. Fan aspects of it too, I enjoy, of course. It’s nice when scholarship and fan culture can come together.

JL: Personally, that’s my favorite thing. I enjoy the fact that you can study these things that you may be a fan of on a personal level.

I know that part of your expertise focuses on pre-war Modernist Japanese texts. Was that a deliberate choice because you enjoy the work? Or is it just enriching in that specific area of time within the culture and history of Japan?

JA: I am really fascinated with Japan during the early 1910s through the late 1930s. Japan had this rich, flourishing culture that absorbed lots of new modern ideas, to the point that just about everything changed. The country had an interesting hybrid culture even before that, but around the 1910s and 1920s, Japan had developed to the point that Japanese artists, writers, and thinkers were just as creative and challenging as the most exciting things happening in the West. I just think it’s a fascinating era; the Japanese Jazz Age was incredibly interesting. There were the Japanese equivalent of flappers; capitalism came in the form of department stores; writers were doing things that would have humbled some of the best Western writers, yet this new culture also butted up right against traditional culture. It was an increasingly sexually liberated time too. There were the beginnings of the feminist movement, and queer writers were emerging. All sorts of interesting authors like Edogawa Ranpo and Jun’ichirō Tanizaki explored these things in their writing.

So, Japan had an increasingly cosmopolitan culture. Japanese writers learned from Western writers and responded to them in their writing. Unfortunately, very few of the Western writers could read what Japanese writers wrote because, of course, the problem of translation. But the point is that Japanese writers were completely up to date with what was happening in the rest of the world. They used what they saw outside Japan as the food for their own culture, and that’s the reason that I rejoice in the early modernist era so much. It was this flourishing moment in history with such dynamism—totally awesome.

Incidentally, the Japanese government had a censorship mechanism in place all the way up through World War II. That meant the government kept detailed records on how many magazines were published at any given moment. I don’t remember the exact numbers off the top of my head, but from around 1910 to 1930, the same period I just discussed, the number of magazines that existed in Japan quadrupled. Suddenly, there were way more magazines and publishing forums.

As a result, there was this explosion of new writers and interesting people, and Kayama, the guy who wrote these Godzilla novellas, grew up during that era. He was born in 1904 and grew up surrounded by this profusion of new writing. Kayama read about paleontology and science while also reading fun stuff like the wild writings of Edogawa Ranpo, the quirky writer that I mentioned earlier. He loved stories about the bizarre and weird, which flourished in the 1920s and 1930s. And so, later on, his work reflected those interests.

My interest in kaiju might seem sudden to people who just know me academically. They may question my reasonings for jumping from serious, “high lit” writers to Godzilla. But Godzilla is aesthetically related to the stuff I’ve spent so much time analyzing. The writers and creators of kaiju eiga grew up reading these things. They’re all connected.

JL: How interesting! Historically, it’s the next step. Because, I mean, we’ll get there a little bit further on when we talk about Godzilla directly, but I would say, it’s quite the milestone picture in film history. Even if you’re not into the rubber suits and stuff, it’s such an important cultural milestone for Japan, and such an impactful film that kind of changed everything.

Right? I mean, you can go anywhere in the world, and people know about Godzilla. Funny enough, earlier this year, I was taking a personal trip to Guatemala to see the Mayan pyramids and travel in the highlands. I went into a shop with super vintage-looking t-shirts hanging all over the place, and I saw one of them had a vintage Guatemalan drawing of Godzilla on it! It was part of a series of shirts showing vintage labels of Guatemalan products. Apparently, there was a fireworks company that had one extra-big firecracker called El Gran Gotzilla. I thought to myself, wow! Godzilla left in impression everywhere, even Guatemala! How many other Japanese cultural products can you say that about? Godzilla had that wide a reach. It’s so, so broad—the big G is just awesome that way. So I love to think about why people delight in it so much too. It’s such an interesting question.

JL: I love asking people that question too! I’m a little interested in how you tackle post-war media because I was reading your afterward in these Godzilla translations, and it kind of mentioned that the occupational period was different compared to the censorship you’d see from the Imperial era of Japan. Could you perhaps elaborate on that a little more? I wouldn’t say it was more extreme, but perhaps, different, I guess. Do you think that kind of influenced the shift from this modernist textual movement into poetry becoming more popular? Or was there something else going on?

JA: Censorship was heavier under the Japanese Imperial regime than it was in the postwar period, for sure. For example, in the 1920’s the Japanese censors really cracked down hard on socialism, communism, anarchism, and any kind of leftist ideology that wanted to work against the Japanese empire, which was busy exploiting the masses and taking over more and more territory. The leftists were virulently opposed to these things. And so, to the Imperial Japanese government, socialism was enemy number one, and during the 1920s, leftists were so persecuted that many renounced their ideology just to live.

When World War II ended and Japan lost the war, the Allied Powers took over. Interestingly, the Allied Powers changed the mechanisms and aims of censorship. They recognized that that one of the problems that contributed to World War Two was that there wasn’t enough diversity of voices in the Japanese media world. The Allied Powers wanted to provide more space for people to be oppositional, so they stopped censoring ideology. It was okay to mention communism and socialism under the American-led Allied occupation of Japan, which lasted from 1945 to 1952. However, others things were censored, especially overt criticism of the Allied forces. In conjunction with that, they censored open discussion of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, because they thought that open discussion of the atomic bombings could potentially poison the hearts and minds of the Japanese population against the occupying Allied forces.

Godzilla comes along in 1954, not tremendously long after the end of the occupation in 1952, so really, the end of occupation-era censorship was still fairly new. That meant that by the time that Godzilla was made in 1954, there were practically no movies that that openly dealt with the formerly taboo topics of nuclear weapons and radiation. There were there was only a handful of them, and they tended to be mournful and not as critical as we might expect today.

JA: Yeah, they’re a little subtle about it, I think, is what you were kind of getting at in the afterward you wrote. There wasn’t outright protest filmmaking happening on the blunt scale.

JA: Right, right. Part of that had to do with the studios themselves. They didn’t necessarily want to make protest films. How many people go out and watch a film about big social issues during an era of hardship, when going to the cinema was still a bit of an extravagance? The number of people who watch movies on social issues will always be more limited than people who go out and watch big blockbusters. When Toho Studios came up with the idea of making a movie about a radioactive monster, they gave the story idea to Shigeru Kayama, hoping that he could make a workable story that people would really want to see. But Kayama really did want to use the opportunity to write about radioactivity; he wrote a long introduction to the first scenario in the film that openly decried the evils of the nuclear weapons.

JL: Oh yeah, the opening narration in there that you placed in the afterward for context was mind-blowing. It said something close to “On this day in 19XX, the US conducted their Castle Bravo test and blew up an island near Japan.” It did not beat around the bush whatsoever.

JA: He really wanted to use the film for political purposes. The people at Toho studios got his scenario, and I think that they all thought that it was way too heavy-handed for a popular movie. So, they lightened up all the very explicit anti-nuclear stuff in the original scenario. The producers, directors, and studio folks got together and scratched their heads. They discussed and rewrote his ideas into a workable movie, changing a lot in the process. Interestingly, Kayama stayed on board with the changes, and it doesn’t seem that he really opposed them. In fact, he loved the movie when it came out. It’s said that when he watched the movie for the first time, he burst into tears because he was so moved by the entire experience. But later, when he wrote the Godzilla novellas that I’ve just translated, he stuck back in at least a little of that the blunt anti-nuclear messaging that he had originally wanted to put in screenplay but that got taken out.

JL: There are quite a few differences there, too. I specifically wanted to point out the Tokyo Godzilla Society subplot. I don’t want to call them a cult, but there’s a propaganda campaign revolving around Godzilla that’s being posted around town. Kayma keeps bringing up throughout the course of the plot. Perhaps a commentary on people’s weird schemes in wake of disasters?

JA: Right. That was my reaction when I read the book for the first time. What is this addition of a subplot that’s not in the movie? What was Kayama thinking? This isn’t in the movie at all. Where did it come from? And, you know, I’m not sure that I necessarily have a great explanation for why he added this subplot. But I’ve come up with a couple of theories. One of them is if you go back and watch the ancestor of all the kaiju films, King Kong, there’s a group of people that worship King Kong as a living god. And so, I wonder if Kayama was remembering that.

JL: I think I agree with that theory.

JA: Certainly, King Kong was on the mind of the filmmakers; there’s no question about it. King Kong was made in the 1930s. But then, just a few years before Godzilla came along, it was rereleased in the United States, and it raked in tons of money, showing people that films about big monsters could make money. That didn’t go unnoticed in Japan. But an even greater influence on Godzilla was another film from 1953: The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms.

JL: Yes!

JA: Tomoyuki Tanaka, the producer at Toho studios who originally came up with the idea for a film about a radioactive monster, was very aware of it. He was flying home on an airplane in 1954 from Indonesia to Japan. And he was looking at a magazine, which had an article about The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. He thought, well, this is an interesting idea. I wonder if we should think about making a monster movie?

JA: I’m sure many of your readers know this story already, but Tanaka had been planning to film a movie in Indonesia. It was a movie about a Japanese soldier collaborating with the Indonesian independence movement, but in 1954, the political relations between Indonesia and Japan soured. And so, Toho lost their permits to film in Indonesia. Suddenly Tanaka, who had to produce a film for Toho that year, had to come up with a new idea. What am I going to do? So, he was flying back from Jakarta, looking at a magazine, when came across an article about American monster movies, and he thought, I wonder if we could do something similar to that? I don’t think he realized at that moment that this idea would turn into the most expensive Japanese film ever made up until that time.

JL: I just want to make a quick, cheap monster movie and then… the budget just went ka-boom!

JA: Exactly! As the project grew and grew, he got completely freaked out. Everyone at the studio was thinking uh-oh. We’ve never done a film like this in Japan. We’ve never made a movie this expensive. Are people going to come and watch this thing? I have read that the wife of the director Ishiro Honda recalled that for months, Honda walked around fretting. He was on pins and needles wondering, “Is this going to be the end of my career? Spending all this money on this movie? What am I doing?” But as we all know, it worked out.

JL: As an academic and scholar going into Godzilla, did you do any contextual reading to prepare? Did you read Steve Ryfle and Ed Godziszewski’s Honda biography? Your translations also mention William Tsutsui’s Godzilla on My Mind, was that also a source you examined going into this project?

JA: Let me back up a second… One of my motivations for translating Godzilla and the Godzilla Raids Again came from the fact that I was in Japan during 2011 when the when the Fukushima meltdown happened. And like everyone else in the country, I was really freaked out. I got really worried. We were all really scared. And even after I came back from the United States, that fear and worry continued to weigh on my mind. And so, I and many other Japanese literature professors started teaching classes about disaster in Japanese culture.

I decided to put Godzilla on the syllabus. At first, I put it in for fun because I enjoy the film and it was a nice break from some of the other very heavy things we were doing in the class. Plus, Godzilla draws students! (Laugh) At that time, I hadn’t done the academic work yet. I hadn’t read all of Tsutsui’s wonderful work on Godzilla yet. I hadn’t read [Steve] Ryfle and [Ed] Godziszewski’s Honda biography yet. But as I showed Godzilla a couple of times, in my class, I was struck when I was watching the credits. It said based on the work of Shigeru Kayama. I knew he was an important science-fiction author, and thought wait, hold on a second… Based on his work? There’s a novel? I wondered, what was his role in it? And so, I started looking around.

In same classes, I used chapters Godzilla on My Mind to get students thinking about Godzilla in different ways. You know, rather than just “big lizard smashes building.” There’s lots of wonderful scholarship about Godzilla, but hardly any of the scholars mentioned Kayama and his role in the genesis of Godzilla. After recognizing that, one, Kayama contributed to the birth of Godzilla, and two, that his contribution is not well known here, I thought, there’s work to be done. I got the Japanese book right away. When I read Kayama’s novelizations, I was blown away. It’s incredible that nobody had done an official translation yet for Western audiences.

JL: It’s far, far overdue.

JA: Right? After I got done with Godzilla, the first novella, I found out that there is a fan translation of it online. So, I want to give a nod to the author of that fan translation, which was quite good in several places. But to the best of my knowledge, there was no fan translation of the second Godzilla novella “Gojira no gyakushū,” usually translated in English as Godzilla Raids Again—although a better translation might be “Godzilla Counterattacks.” I’m so happy that we could bring them out in a single, handsome volume.

JL: Regarding that, I was really interested in that story Kayama tells where he’s kind of stuck on what to do with a follow-up to Godzilla. Where do you go from here? The Oxygen Destroyer was used. Godzilla is dead. How is there a part 2?

JA: There’s zero question at the end of the first film that Godzilla was destroyed. Fans know that the iconic Oxygen Destroyer had eliminated the creature for good. But from day one, Godzilla was a massive success in theaters, and bigger than they had even anticipated at Toho. People lined up around the block at the Nichigeki Theater, one of the big movie theaters in Tokyo. It struck a chord with people of all generations, not just kids who loved the dinosaur aspect, but adults too, who remembered their own experiences in World War II. The film was cathartic for them, as they remembered their fear and their anxiety, and many audience members related in a very deep personal way to the to the film.

So, Toho came back to Kayama, requesting him to do another Godzilla movie. Kayama at first was confounded by this prospect. He had killed Godzilla. The story was over. He wondered, what the hell could we possibly do? But then he decided to capitalize upon the fact that at the end of the first movie, the paleontologist Professor Yamane says we must be careful. If humans continue this sort of dastardly hydrogen bomb testing, who knows if another Godzilla might appear? Kayama recognized that comment was his way out of the conundrum.

There’s an interesting story. I’m not sure exactly when it happened, but according to an article that Kayama wrote, he was in a dentist’s office at some point after the release of Godzilla Raids Again, and there happened to be a Life Magazine there with some pictures of dinosaurs. A kid who happened to see it there got all excited and exclaimed “Oh, look, look! Godzilla! It’s Godzilla!” Hearing this, Kayama realized the Godzilla story he had created had a different impact on people than he had originally anticipated. People loved Godzilla. He had originally intended to use Godzilla as a kind of anti-nuclear story, but things had shifted. People had developed an affection for the monster. He had wanted to Godzilla to serve as a stand-in for the horrible threat of disaster hanging over Japan and the world, so his experience in the dentist office made him realize that maybe he hadn’t achieved his own goal. In the second movie, his anti-nuclear message didn’t really come through—it was the kaiju battles that took center stage. So, he decided that he was never going to write another Godzilla film again. Ironically, he ends that article by noting, “I must admit that even I had started to feel affection towards Godzilla too.”

JL: That was a quote that stuck with me a lot. It was interesting for Kayama to remark about some affection brewing. He started to feel it a little. Maybe it’s not so bad.

I also love the story behind how he decided to kill Godzilla a second time, too. It got a little chilly on his holiday, so he decided the proper response was an avalanche.

JA: Ha-ha, that’s right! He didn’t have much time to sketch out the ideas for the films. He turned around the scenario for both the first and the second films incredibly quickly. I don’t know exactly how much time the studio gave him for the second film, but he did most of the work for it in around a week. He was really ticked off because it was right around the end of the year, and all his friends were having celebrations and taking vacations. Meanwhile, he’s stuck doing this project, thinking of a good way to kill Godzilla again. He was at a resort at Atami, and it was really cold outside, so from that, he derived the idea of killing the second Godzilla with an avalanche of ice.

JL: Regarding the translation itself, the first thing I picked up on when I started reading it was the lack of Ogata. In his place was Shinkishi, the young boy that acts as the tour guide on the island in the original film. Was that because these novellas were aimed at a more adolescent audience?

JA: Yeah. Just to clarify for readers who might not remember the names, in the film version, which came first, there’s a character named Shinkichi. He’s a small boy in early adolescence who serves as the guide to the characters. He hangs out with them and shows them around Odo Island when they go investigate Godzilla’s origins. But he’s, for the most part, a secondary character. In the novella version, Shinkishi has taken over the role of Ogata, the lead in the film, played by the late Akira Takarada, as a main character and Emiko’s love interest. When he wrote the 1955 novella, soon on the heels of the second movie, Kayama reassigned Ogata’s role to Shinkichi. The 1955 novella was published as the first volume in a series called “Shōnen Bunko,” or in English, “Youth Library.” Just that makes it clear that he was aiming for a young, largely male audience, and so perhaps it was appropriate to put Shinkishi in the center of the plot.

JL: Perhaps an avatar protagonist was needed for those readers. I would agree with that completely!

Also, within the translations, I was particularly interested in Kayama’s frequent usage of sound words and how, how much he’s a fan of doing that… it’s very impressive. I think you said that with a lot of these sound words there’s not really an English equivalent per se.

JA: That’s right. The Japanese language has a lot of sound-related words… Way more than English! I mean, of course, we do have a lot of sound-related words in English; for instance, the word “buzz,” which we will use as a verb, represents a sound—a “bzzzzzzz” kind of sound, but Japanese has far more sound-related words than English.

The book, I think, is delightful in its usage of onomatopoeias. Do you know how you visualize things in your mind as you’re reading? The book doesn’t just give you the visual description typical of most novels and novellas. It also gives you a lot of auditory descriptions as well, especially in the scenes where Godzilla is stomping through Tokyo. There are all kinds of sounds; there’s a sound in practically every sentence. There’s a CRASH, and then a BOOM, and maybe a KAPOW or the Japanese equivalent of those things. I quickly found myself struggling to come up with good equivalents of all the words Kayama uses. One distinctly Japanese word that he uses a lot is MERIMERI, for example, “The building crumpled, MERIMERI.” The word MERIMERI represents the sound of something crumpling up like an accordion, such as when a car crashes and the whole front of it gets smushed. That sound. It was hard to think of a real English equivalent. Obviously, I couldn’t put the word MERIMERI in the book verbatim; no one would know what the hell I was talking about.

When I first showed the very first draft of this to my students and asked for their impressions, they were fascinated with how many sound words there were. I did my best to try to keep as much sound as I could. Honestly, there were moments when I thought all the sound words began to sound ridiculous.

JL: How was that balance between really maintaining what was originally there, and making some of the changes that need to be there through translation for Western audiences? Did you end up being more traditional, or did you appease any Western conventions, especially within Godzilla’s realm?

Obviously, I had to make the Japanese fit English. But because this is a book that was written for young people, it was a lot more concrete than some other texts might be. There’s a lot of descriptions in the text of how people looked, what they did, what they said, and so on, and those don’t require a lot of cultural adjustment. However, there were times when I stepped in to add some cultural information that was missing. I debated long and hard about how to do that, because I have a distaste for sticking my hand into a text too much, nor do I really want to add stuff if I don’t have to. I debated with my editor and pondered for some time. Should I add footnotes? That might make the book too academic-looking for young adult readers, so I had to find another solution. I decided on adding a glossary of place names, proper nouns, and so on to the end of the book so that interested readers could peruse them if they wanted.

Very frequently, Kayama mentions different branches of the Japanese government—the Maritime Safety Agency, as one example. I realized that American readers might not know what that is, so I put an entry about it in the glossary. Maybe it would be interesting to readers to know that this was the equivalent of the Coast Guard at the time. In fact, this same agency changed its official English translation in 2000 to the “Japan Coast Guard,” but I wanted to get the language right and use the words that would have been used in the 1950s, not the ones used today. That meant I had to do research on the history of the official translations of these various government agencies. The glossary became a place where I could mention those little pieces of cultural and institutional history.

Another example. In the film, Godzilla smashes all sorts of buildings, but in the novellas, Kayama focuses his description on the destruction of certain, particular buildings. It was interesting for me to think about what buildings specifically were destroyed, and why those buildings? What did they represent to Kayama and to moviegoers in 1954 and to readers in 1955? For instance, Kayama spends a lot of time describing Godzilla smashing a particular bridge in Tokyo, the Kachidoki Bridge. Why that bridge? I always think about details like that. I wrote about that in the glossary too. Readers can decide to ignore the glossary if they want, but kaiju fans can read the glossary and get all nerdy along with me if they want.

Can you break down why that bridge is so historically significant?

JA: So, the Kachidoki Bridge that Godzilla stomps upon was created during the most nationalistic days of Imperial Japan. The Japanese government created an island in Tokyo Bay with landfill islands to host a right-wing, nationalistic exhibition, on what the government had decided was the 2,500th anniversary of the founding of Japan. It’s hard to say when Japan was actually founded because that’s all wrapped up in mythology in Japan’s earliest books. Plus, empirical evidence contradicts what was written in the earliest books about the founding of the Japanese state. But anyway, one of the ways the Imperial Japanese government tried to show the legitimacy of the Japanese Empire was to say, look, we’ve had an imperial dynasty that has lasted longer than just about any place in the world! We’ve been around way longer than the British Empire, way longer than the Russian Empire, we’ve outlasted everybody! The exhibition on the island in Tokyo Bay described the mythology about the foundation of Japan as real history. People who crossed Kachidoki Bridge to go there heard about the mythology, about the mythological founding of the Japanese Empire, thus reinforcing Japanese right-wing nationalism.

I can’t prove it beyond a shadow of a doubt, but I think that Kayama’s specific decision to describe in such vivid detail the destruction of that bridge was that he symbolically wanted to break Japan away from its imperialist, nationalistic past. Like many people in postwar Japan, he recognized that view of history was a tool used to lead Japan into war. Also, the wartime fire-bombing of all the Japanese cities, plus the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki ended the myth of the invincibility of the Japanese spirit. There, he was using Godzilla for the same purposes.

JL: That’s amazing, and truly fascinating.

JA: When it comes to some of the other buildings mentioned in the text, it’s somewhat clear why Kayama has Godzilla destroy them. Namely, one of the things he stomps upon is the Japanese Diet building, which is you probably know, is the home of the Japanese parliament—kind of like the Japanese version of the U.S. Congress.

JL: That bridge insight though, I would have never known that. Could have been just a water-based landmark for all we knew.

JA: And I didn’t know that either until I began to investigate. But I think that viewers in 1954 and readers in 1955 would have remembered the associations with those places. The empire and war weren’t so very long ago—it was in recent memory, you know, that the island was created and the bridge built. They were engineering marvels at the time.

JL: In terms of other challenges with translating Godzilla, there was one that I also found especially fascinating. The choice to refer to Godzilla as “he”. I talked to Graham Skipper a while ago who wrote Godzilla: The Official Guide. He worked directly with Toho on that, and he said the only big notes he got back were to stop calling Godzilla “he”. So, reading that the choice of pronouns was a deliberation and a choice within your translation, I found that fascinating. Toho’s reasoning was “you don’t call an earthquake “he;” it just is an earthquake.” I was surprised to see that you went ahead and presented Godzilla with those pronouns in this translation after considering it carefully, as stated in your afterward.

JA: I’ll bear the weight of that decision. The original Japanese text doesn’t provide any hint—not the slightest clue—what Godzilla’s gender might be. In Japanese, you can talk about somebody at great length and the things they do without ever referring to their gender. You don’t have to use pronouns in Japanese at all, provided things are clear from context. And if you want to clarify who is doing what, you’re more likely to use their name rather than a pronoun. And, and that happens here. Godzilla is just referred to as Godzilla, and a pronoun is never used.

However, in English, we need pronouns all the time. For example, in Japanese, “raised hand” or “smashed building underfoot” would be perfectly complete sentences in and of themselves, provided it was clear from context that Godzilla was doing the action. But in English, you need a subject in every sentence. You have to say, “He (or she, or they, or it) raised his (or her, or their, or its) hand.” I as a translator felt stuck; what am I supposed to do?

When I first went and translated the book, I translated it in a completely gender neutral way, referring to Godzilla as “it,” but when I shared the draft with my students, they rebelled. They responded no, the use of “it” is too impersonal. Too distancing.

So what pronoun to use? I thought about the movies—at one point in the franchise, some eggs appear. So I asked myself, what is Godzilla? A she? A he? Could Godzilla be hermaphroditic like some amphibious creatures? Perhaps Godzilla has no specific biological sex at all? The answer wasn’t clear.

JL: It’s a loaded question that could be discussed for hours.

JA: It totally is. And, you know, here I am, queer activist here. I wanted to make Godzilla gender non-conforming, but I struggled over this one. This seems like it should be such an easy thing to deal with, but it’s not. And I finally came to peace by thinking okay, if Kayama wanted Godzilla to sort of be a stand-in for the nuclear bomb and the anxieties that came along with radioactivity, we have to recognize that the creators of the atomic bomb in the United States were largely men—Robert Oppenheimer and his crew. Historically, men dominated the U.S. military. So, if we’re following Kayama’s assertion at the beginning of the novella that Godzilla is a stand-in for the nuclear bomb created by the male-dominated American military, maybe it’s okay for Godzilla to be a guy.

If it were completely up to me, I’d prefer the gender-neutral Godzilla. I tried using “they” following the contemporary use of “they” to mean a non-gender specific individual. However, that made certain scenes hard to understand. When Godzilla interacted with people, it just got confusing. Does the “they” in the sentence mean Godzilla or the group of people he was confronting? I had thought it might be groundbreaking if I used “they” to refer to Godzilla in my translation, but it often got confusing about which “they” I was talking about, so it introduced all kinds of problems that would be nightmares for copyeditors. It just didn’t work on the page the way I had wanted.

In any case, this is a fascinating problem. Maybe in 50 or 60 years, after the copyright has expired, someone will come along and retranslate Godzilla and do something completely new. New generations often like to retranslate books in ways that speak to them, and I’m all for that.

JL: It would be radically different in some ways, I think. Translation is always changing, I specifically would think about how many translations of important and religious texts have always had their own “take” on what is being said.

JA: Yes, translations always reflect the current moment of the time when they’re produced. But I’ve tried to put aside my twenty-first-century-ness and capture something of the 1950s in the translation. Some reviewers have said that the dialogue sounds “dated,” but to me, that’s a compliment. The book was written nearly seventy years ago, so if it sounded like the characters were living in the twenty-first century, not the 1950s, it would be jarring and strange.

Can you speak about Toho’s potential involvement in these translated releases? Did you have to send them anything for approval?

JA: We weren’t involved directly with Toho because they don’t own the rights to the novellas. I think that the press used an agent to form a contract with his estate, who was managing the copyrights on Kayama’s behalf. Kayama passed away in 1975, so someone has been managing the copyrights for him since then. I had originally wanted to include in the book the scenario that Kayama wrote for Toho as well, but that would be a completely different set of rights negotiations, and so that was out of our purview. So I didn’t translate Kayama’s G-Project scenario, but I did talk about it in the afterword and include one super short excerpt. Overall, I super happy with the way the book turned out.

JL: One quote of yours specifically that I found especially interesting was “Without translation, we would be locked in our own cultures.” I would love for you to elaborate on that a little bit.

JA: One of the one of the biggest problems with our consciousness is that we simply can’t take in information that we don’t understand, right? Although we might not realize it, language is like the walls of an aquarium. Think of us like fish swimming around inside. The inside of the aquarium seems like the entire world for us, but in reality, the boundaries of the aquarium—the boundaries of our language—serve as the boundaries of our consciousness. There are things outside we simply cannot get to, and so we don’t even know that they exist. And usually, people aren’t even aware that there are barriers around them and that there are things they cannot see.

You know, I talk to people all the time who claim that English is the universal language. They think it will get you anywhere—you can read anything, you can go anyplace. And that’s so, so not true! I’ve heard the estimate that only somewhere between 12% and 20% of the world speaks English, and sure, that’s a large number. And sure, maybe there are more English speakers than any other language, but even so, most of the world doesn’t speak English. There is just so, so, so much stuff being produced out there that isn’t in English!

It’s staggering to think that Japan, for instance, has a book publishing industry that’s practically as large as the one in the United States. They publish near the number of books published annually in the States, even though Japan has only half the population. In other words, Japan has a much higher per capita production of books and magazines than the States. Japan has a very, very dynamic book culture. However, only about 25 to 30 books of Japanese literature are translated every year in North America. Those statistics would be higher if we include manga, but even so, it is still a tiny number, especially when you consider that tens of thousands of books are being published annually in Japan. It’s very easy to assume that we’re getting all the best stuff in English, but that is downright wrong. In the English-speaking world, we see only the tiniest tip of the iceberg.

JL: There’s a huge influx of manga coming into the US, but prose writing? Absolutely. I think your book was my introduction to translated Japanese prose.

JA: That’s great to hear. Translating novels takes a long time. I’ve got friends who translate manga professionally, and it seems like they churn out the translations really quickly, maybe because there are so few words on the page, but with novels, there’s nothing but words. It takes a lot of time, and that’s one reason we just get the tiniest drop in the bucket. So, there’s all this stuff out there that English readers don’t see.

And I’m just talking about Japan here! When you think about all the other languages in the world, and all the other book publishing industries out there in the world, you realize how little we get! I really think it’s a terrible embarrassment that we in America aren’t more interested in what people in the rest of the world are doing. People out there in the world are doing incredible things. Sometimes the most creative, amazing works come from the corners of the world where Americans are not looking.

JL: Absolutely, and it’s so enriching within Japan specifically. That was my biggest light bulb moment when preparing for this interview. With anything we’ve discussed in the realm of Japanese media, it’s about life after disaster; no matter if it is Godzilla, or a world-class drama from acclaimed directors of this time, be it Kurosawa, Ozu, or somebody else.

JA: Absolutely. All of these works raise fundamental questions about what it means to be human. What kind of ethical dilemmas do we find ourselves in? And how do we manage to live ethically and move forward? What could be more human than that?

JL: Godzilla and kaiju adjacent media specifically, what does it mean to you? How has it impacted you?

JA: I’m especially fascinated with kaiju because, well, at the very core, they’re exciting stories. If you’re only watching Godzilla because you’re interested in watching people react to big monsters, that alone is interesting and fun. But we can also look at them more deeply, asking ourselves why these stores are being created. Why do kaiju appeal to us so much?

I think that one reason that kaiju stories, and Godzilla in particular, appeal so much to me as a literary historian and translator is because of the interesting ways that reflect cultural history. The films tell us a lot about cultural issues in Japan at the time. For instance, if you watch the 1971 movie Godzilla Vs. Hedorah, one of my favorite kaiju films, it’s clear that the sludge monster in the film was inspired by the recent industrial pollution incident in Minamata, Japan, where a company called Chisso poured tons of toxic sludge into the Ariake Sea, poisoning thousands of people and killing a shocking number of innocent fishermen. This horrifying incident affected the country deeply, helping to give birth to the modern environmentalist movement in Japan. The Minamata problem made headlines for years, and so perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that pollution took on the form of a sludgy kaiju in this movie.

Another example: if you watch Shin Godzilla, you can see a really interesting reflection on the unbalanced relationship between Japan and the United States in the early twenty-first century, as well as criticism of the Japanese bureaucracy, which fumbled its handling of the Fukushima meltdown.

In short, there’s always a lot going on in the kaiju stories. Even though you can find a lot of fun in them, that’s not all there is. I love the fact that we can relate to kaiju stories in so many ways.

JL: You’ve tackled poetry and adaptations of classic modernist work…where do you go after Godzilla?

JA: It’s quite interesting, in the wake of this Godzilla project, quite a few individuals have approached me and have said hey, we hope that you translate Mothra and the Luminous Fairies next. For those that don’t know, yes, Mothra was based on a book. Honestly, that prospect hadn’t even crossed my mind until someone mentioned it to me, so, on my next trip to Japan, I got the book and, and I’ve sent off inquiries regarding the rights. It would be lots of fun to do that book. I haven’t heard back, but I hope it’s possible.

I’d also be interested in doing a book of Kayama’s other work. He was a well-known science fiction author before Godzilla entered the picture, so there’s lots of material. You see lots of Godzilla-related motifs in his stories—lots of big monsters that attack humanity when they get attacked. I think the thematic similarities to Godzilla are appealing, and I suspect some kaiju fans out there would really dig his other work, too. Kayama, man of monsters, ought to be better known outside Japan.

JL: Hopefully, we see more Kayama exposure in the United States! As a fan, and as a person who cares very deeply about kaiju media and it being seen and brought to light, I am very excited for what you do next. I for one, think this translation is incredible. And I thank you for hopping on with me and talking about Godzilla, cinema, and being an academic. It’s been a really engaging conversation, Jeffrey and I really thank you for that.

JA: Oh, thank you, Jacob. I had a lot of fun talking with you today and sharing all my passion for this project!

Book Pre-Order Links:

University of Minnesota Press

Amazon

Barnes & Noble

About Jeffrey Angles

“Dr. Jeffrey Angles is a professor and advisor of Japanese in the Department of World Languages and Literatures at Western Michigan University.

Angles’ lifelong interest in Japan and Japanese literature began when he went to southwestern Japan as a 15-year-old exchange student. Since then, he has gone to Japan multiple times, spending many years working, and studying in various cities including Saitama City, Kobe, and Kyoto. Much of his critical work has focused on expressions of ideology within 20th century and 21st century literature and film from Japan. His study of representations of same-sex desire in the literature of the interwar period was published in 2011, and his study of poetry written in response to the 2011 disasters in Japan was published in 2016.

Angles is a prominent translator of modern Japanese literature, with several volumes of Japanese literature in translation to his name. His book “Forest of Eyes: Selected Poems of Tada Chimako,” published by the University of California Press, received both the 2009 Japan-U.S. Friendship Commission for the Translation of Japanese Literature and the 2011 Harold Morton Landon Translation Award from the Academy of American Poets. Other translation projects have earned grants from the PEN America and the National Endowment for the Arts, including his most recent accomplishment of receiving a 2020 Literature Translation Fellowship from the NEA. He has led translation courses and workshops at the University of Tokyo and the British Centre for the Art of Translation.

Angles is also a poet in his own right. His book of poetry written in Japanese, “Watashi no hizukehenkōsen” (My International Date Line, 2016) won the Yomiuri Prize for Literature, making Angles the first American ever to win this prestigious prize for a book of poetry.”

– Western Michigan University