GODZILLA MINUS ONE

“Why am I alive, while others are dead?”

It haunts all of us, the great question that has no answer. None more so than survivors of war. And none more literally than a survivor of a Japanese Special Attack Unit, aka “kamikaze.”

And that is our viewpoint character in Godzilla Minus One, the new film by Takeshi Yamazaki. Koichi Shikishima, played by Ryunosuke Kamiki, chooses life twice over in the film’s prologue and returns in disgrace to firebombed Tokyo in 1945. Then he chooses life yet again, by refusing to abandon a woman (Minami Hamabe) and an infant to starvation. At every turn, he’s castigated by society. But there’s nothing wrong with Koichi, and everything wrong with society.

Godzilla Minus One is an angry film, but the subject of that anger is not always quite what you’d expect. The USA–victor of WWII and garrisoning power of Japan in 1947, is alluded to with a light touch. The US Navy’s irradiation of and subsequent clashes with Godzilla are handled with a perfunctory montage that looks straight out of one of Legendary Pictures’ “Monsterverse” films, and afterward they are only defined by their absence. The Japanese government, which (eventually) successfully defended Japan in 2016’s Shin Godzilla, is more archly dealt with here. Not only are they useless in the present, but they created the culture of death that led to the kamikaze in the past, and they are implicitly blamed for failing to defend Tokyo from the firestorm that consumed so many families.

It’s the connections that Koichi creates at home and at work that lead the way out of the blackness in his soul. The film invites us to imagine the weight of survivor’s guilt when reinforced with explicit disgrace from his peers for failing to immolate himself uselessly against the American war machine. His trauma lingers even as the world around him moves on from the war, and prevents him from seeing the obvious way to move forward with his life. Rather, he wallows in self-pity and self-denial. What he, and we, are asked to accept is that destroying yourself pointlessly is not courage, and refusing to is not cowardly.

And then, there’s a monster.

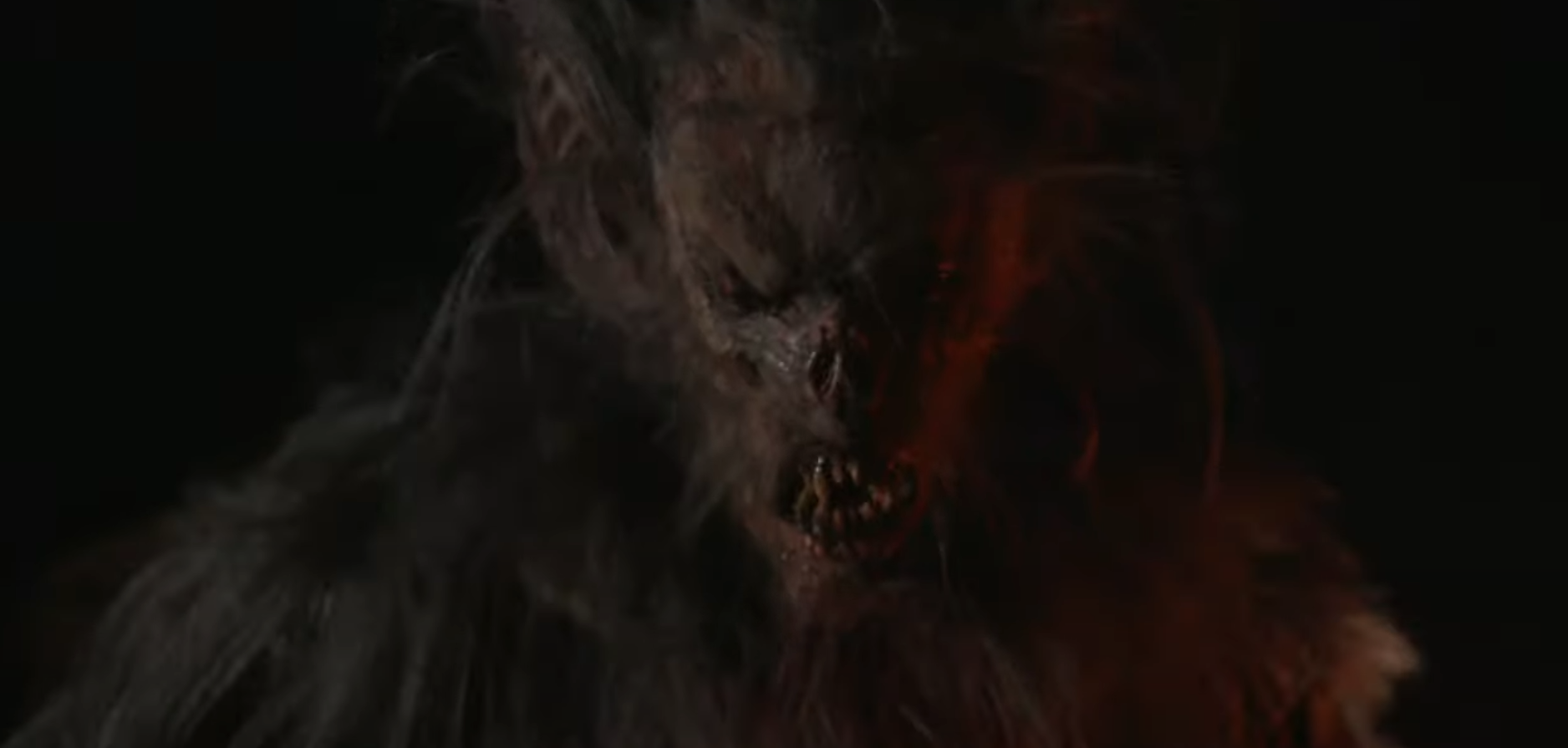

Godzilla Minus One is a fine personal melodrama, but it will be remembered for how it handles the titular character. He’s just…there. Not seen from miles away, not some impossible largeness separated from cowering extras by the impenetrable shield of bluescreen. He’s right in front of you. Fifty meters tall.

Godzilla himself, visually speaking, is something of a pleasant amalgam of various aspects and features from Godzilla 2000, Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (1991), GMK (2001), and Godzilla (2014). But he has the ruthless and aggrieved nature of the original 1954 Godzilla, and he’s simply there, in 1947. No one can stop him; they can barely even comprehend him. His body is a mass of scars, his newfound bulk difficult to drag across the land. By using a “conventional” Godzilla, but in a period film, fully utilizing modern VFX to transcend the limitations of typical tokusatsu, Yamazaki creates an alarming effect. The film is able to lean onto our knowledge of Godzilla in order to cut out any ponderous exposition and avoid repeating beats of the scientist-and-politician-heavy Godzilla (1954). This keeps the focus of the film where it belongs, on Koichi’s emotional journey. And as a secondary focus, there are the Herculean efforts of a community of burnt-out veterans to deal with a monster that is not only unstoppable, but able to unleash the power of the atomic bomb on whatever it sees.

Yamazaki generally avoids explicit references to the atomic bomb but its implicit power is imbued in Godzilla’s scarred appearance, and in his terrifying heat ray. In a haunting scene, Koichi bears witness to the atomic destruction for which he was absent in 1945–with the additional horror that it may be his fault. Koichi becomes an avatar for not just survivor’s guilt but the fear of failure–Japan’s fear of losing the war and becoming subjugated or worse.

But as Koichi’s own situation illustrates, Japan may not have deserved its fate at the hands of US bombers, but they didn’t deserve to win the war either. While there are no references to Japan’s atrocities against other nations, even in the veiled way that Shusuke Kaneko’s GMK broached the subject, the Imperial government’s moral unfitness is demonstrated by its treatment of Koichi and the other veterans.

But Godzilla Minus One not only draws clear lines against warmongering and neglect from the central government, it expands that into opposition to the glorification of death and sacrifice in general. As Koichi becomes more and more sure that he must trade his life to destroy Godzilla and atone for his sins, his friends become sharper in their opposing conviction not to spend lives. Due to the scale of the problem, surplus resources from the war are pressed into service, but the film is pointedly clear that the actual military is useless, while the efforts of private citizens are productive, clever, and compassionate.

It’s hard to talk about this without spoiling elements of the climax, but I don’t feel Yamazaki’s message is fully realized without contrasting this with the other series films. Memorably, Godzilla (1954) ends with a human sacrificing himself to save others. Similar beats recur in Godzilla Raids Again, Shin Godzilla, Godzilla King of the Monsters (2019), etc. Here, the anti-Godzilla volunteers bravely accept the possibility of death, but just-as-bravely refuse to engage in a plan that includes the certainty of death. Yamazaki challenges Koichi and the audience to persevere through horror by believing in one’s own inherent value.

As for Godzilla, ultimately, he’s little more than the unstoppable force upon which humanity is tested. This isn’t unusual for one of Toho Studios’ darker takes on Godzilla. If you are interested in Godzilla as a character with an internal life, that’s the aspect that the Legendary Studios’ Godzilla (2014) and its sequels have successfully depicted. For better or for worse, Godzilla’s relative flatness as a character is underscored by the rearrangement of classic Akira Ifukube tracks to represent him–spectacular-sounding, but distractingly incorporating the leitmotifs of Kong and Mothra seemingly just because they were in the original tracks. Godzilla isn’t afforded much grace or compassion from the cast either (barring one brief, almost out-of-place moment), despite being a victim of both Japanese encroachment and American fecklessness. Like the original film, however, layers may be revealed by repeated viewing. It may be noteworthy that Godzilla only uses his fearsome heat ray in response to direct attacks on himself. At any rate, the spectacular way in which the monster is visually realized will more than reward such repeated viewings and indicates the passion that Yamazaki has for Godzilla’s many past incarnations.

Despite its 1947 setting, Godzilla Minus One’s anti-war passion feels more timely than ever as we witness savage urban destruction in Ukraine and Gaza today. On a personal note, as a new parent, the storyline with young Akiko was a gut-punch that had me uncharacteristically bawling in my seat. As hard-hitting as the movie is in content and imagery, it is ultimately affirming, with a core of good faith and humanism. It proposes that, while we will never answer the question of “why us and not others,” we can save ourselves by not yielding to despair, and precisely by doing this we also save those who are closest to us.

Being a Godzilla fan often means accepting moments of beauty in films that are flawed. Even the 1954 classic has its issues. In that context, the quality and artistry of this film truly stand out. It would be premature in the extreme to judge Godzilla Minus One as a masterpiece. But I can be confident that in the years to come it will be a staple of top 10 lists in the G-series…and not in the bottom half. This film isn’t perfect, but it certainly exceeds expectations on every level, even over and above the lauded Shin Godzilla seven years ago. Both the all-too-realistic period drama and the action-packed science fiction plots interweave and reinforce each other, while independently being compelling and well-crafted. I’m happy to recommend Godzilla Minus One to anyone from diehard kaiju-philes to general movie buffs. See it, in the theater if at all possible.

I saw this movie yesterday on Netflix. I WAS AMAAAAZIIIING!!