Originally published in Kaiju Ramen Issue 9.

Introduction

When a film shakes the world as much as King Kong did, there will be people attempting to capture the magic found in that original film, and some filmmakers may try to create their own original works inspired by it, while others will take it as a chance to retell the story at a lower budget with the hope of striking it big. The latter, if done enough, could create its own subgenre. Some of these “Kongsploitation” films have been forgotten, some of them have become the butt of many jokes, and some have just been ignored.

Kingu Kongu

The earliest of these came in 1930s Japan when Shochiku (one of Japan’s five major studios and the company that distributed the original 1933 film in Japan) produced a comedic short film directed by Torajirō Saitō with a human-sized gorilla featuring men-in-suit effects titled Japanese King Kong (Wasei Kingu Kongu) that has somebody dress up as the titular King Kong and perform in a stage play to earn money. It was approximately 30 minutes in length and played before the original in Japanese theaters.

A few years later in 1938, as a way to market in on the reissue of the 1933 film in Japan, a two-part silent film known as King Kong Appears in Edo (Edo ni Arawareta Kingu Kongu) was released as an Edo period piece again using men-in-suit special effects. While ape suit maker Fuminori Ohashi (who would later create the yeti suit for the 1955 Ishirō Honda film, Monster Snowman, or Half Human) claims the ape to be Kong-sized, this has been contradicted with marketing for the film. As mentioned, the film was two parts (or episodes) with the first being released March 31, 1938, as King Kong Appears in Edo: The Episode of the Monster and the second episode premiering April 7 as King Kong Appears in Edo: The Episode of Gold.

Both of these Japanese King Kong films were lost; probably due to poor preservation and World War II (most Japanese films prior to 1945 are considered lost). This is a shame as these two films, while maybe not featuring kaijū-sized monster action, fall into the same category as The Great Buddha Arrival (1934) as kaijū precursors to the 1954 classic Godzilla.

Image from IMDb

Ape Suit Manham!

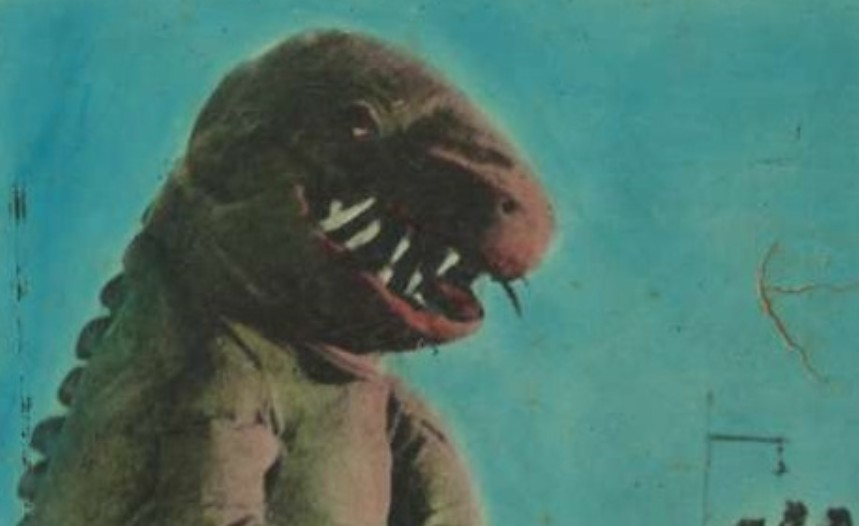

In the early days of Hollywood, filmmakers worked hard to preserve their individuality and refrain from revealing trade secrets behind production, which is why the effects team behind King Kong were also the ones responsible for the effects in the 1925 stop-motion dinosaur film, The Lost World. Audiences rarely saw films with this level of complexity in their special effects, and because of this, in 1948 Jack Bernhard decided to take the basic storyline of the 1933 classic, included more dinosaurs, and removed the last act set in New York and create a brand new film (I guess) called Unknown Island. It lacks the charm of stop-motion and clever mirror tricks and replaces them with stiff dinosaur suits shot separately from the humans to preserve the idea of scale. The film follows a ship crew finding an island filled with dinosaurs and, you guessed it, a giant sloth (probably to prevent any lawsuits). The sloth helps the crew by saving them from a tyrannosaurus rex. The film is now in public domain and is easily accessible. Moreso, fans of the Godzilla franchise may recognize some clips from this film as footage shown to Shoichi Tsukioka and Koji Kobayashi as they discovered the origins of Godzilla and Anguirus in Gigantis, the Fire Monster, the American edit of Big G’s second film, Godzilla Raids Again. Abbott and Costello would also encounter one of these “relatives” to King Kong briefly in Africa Screams. However, this would only last one scene.

That Wasn’t The Plan!

Speaking of men-in-suit action, the plan wasn’t always to just do two King Kong movies and wait for others to copy it; all the major minds behind the original created ideas for King Kong. One was Willis O’Brien. Following the King Kong duology, he wanted to bring the Eighth Wonder back to life in new adventures, but unfortunately due to a lack of interest or money, none of his projects ever got off the ground. That was until John Back bought his King Kong vs. Frankenstein (or Prometheus) story and then turned around and sold it to Toho for what would become King Kong vs. Godzilla.² Even after that film’s success, Tsuburaya would later reuse the King Kong suit in his very first television series under Tsuburaya Productions, Ultra Q (1966), in the second episode, “Goro and Goroh.” Similar to Bela Lugosi (Dracula, White Zombie, Bride of the Monster), who slowly lost all his will to live after being stereotyped for acting roles), Willis O’Brien could never really use his stopmotion skills again.

So, while it’s amazing to see the reach King Kong has had on the world, nearly every wannabe would be made using men-in-suit effects—the very technique that helped lead to the extinction of stop motion (with help of animatronics and computer-generated graphics, of course). One instance where stop motion would be preserved was in the 1967 musical comedy that Rankin/Bass and Embassy Pictures co-produced harkening back to the classic era of Universal monsters such as Frankenstein (1931), Dracula (1931), The Wolf Man (1941), among others, in Mad Monster Party. One particularly interesting character was simply known as “It.” “It” ended up being a giant ape that climbs to the top of a tower where it holds the female character, Francesca, in the same vein as King Kong.

International Apecapades

In 1961 England attempted their own King Kong film and didn’t care whether or not it was obvious: Konga. The story follows an evil Michael Gough (who would later play everyone’s favorite butler, Alfred, in the late ‘80s and ‘90s Batman movies). This time, the ape starts off man-sized, but thanks to a growth formula the evil scientist gives Konga, he grows until he’s the height of buildings. Herman Cohn was the mind behind the film, being asked for another exploitation film after the success of his prior horror movies. He even went and purchased the rights to the term “Kong” from RKO so he could produce the film without getting sued. The film was co-produced with English company Anglo Amalgamated and US-based American International Pictures (the distribution company for a handful of 1960s kaijū movies).

Konga turned out to be a not-so-successful film, but the comics that ran as promotion before and after the film’s release garnered some success, which led to a five-year run and two side stories. These comics would eventually fall into the public domain . Because of this, during the COVID-19 Pandemic, Brett Kelly and his young son created their own adaptation of these comics: Konga TNT. SRS Cinema (a distributor of independent kaijū films) acquired the film and released it to Blu-ray, DVD, and VHS. The film was poorly received, and many people in the kaijū fandom have claimed it to be “one of the worst things to watch.” I guess exploitation films don’t get better with time….

Outside of England, India had some things to say about kaijū and giant monsters. In the early 1960s, three Hindi King Kong movies were produced, and two of them actually had giant monsters. Directed by Babubhai Mistry, King Kong (1962) features a giant ox at the beginning but no giant gorilla in sight (the ox is apparently a dinosaur). This actually marks the first of many giant monster movies produced in India. While most are lost, this one is available online, if you know where to look. The name “King Kong” comes from the main character, Jingu (Dara Singh Randhawa), who fights the wrestler known as “King Kong” and wins. Because of this, he’s crowned the “New King Kong.” The idea of King Kong being a person’s name would later be brought back in Tarzan and King Kong (1965), although unlike the first film, there is no dinosaur (or ox) fight at the beginning. The name “King Kong” might have come from Hungarian wrestler Emile Czaya, who went by the name “King Kong” when performing, but no sources actually confirm this.

The last of these 1960s Indian “Kongsploitation” films is probably the most “true” to the original King Kong story.Shikari (1963) follows circus workers who set out on a journey in the jungle and find the giant ape named “Otango.” There’s also a subplot about a scientist (named Dr. Cyclops, which is ironic because Schoedsack directed a movie with a character by the same name) turning people into apes (and creating Otango). The film mostly follows the romantic plot between our two main characters (a trope found in many Hindi films). Unfortunately, Shikari didn’t perform well and has fallen into obscurity. Perhaps like the Korean King Kong-influenced Space Monster Wangmagwi, Shikari will see a release in the future.

Decades later, India made a King Kong movie with Banglar King Kong (2010). This is the cheapest entry in this list. The film uses footage from the 1976 King Kong film. Throughout it, the footage changes style and look (probably because it’s a film created with stock footage) until the end where the titular Kong rampages through a city made of actual cardboard. The suit for this Kong is from the nightmares of children (if you thought Minilla was scary, get ready!). The film has not received much acknowledgement in the western hemisphere, although that’s probably good as it would receive similar reception to Konga TNT or perhaps even worse…

Another film followed the idea of apes being experimented on by humans: Kong Island (a.k.a. King of Kong Island). While having “Kong” in the title, it’s “Kong in name only” (KINO, if you will—but not really). Kong Island doesn’t actually happen on an island, nor is there any ape or thing named “Kong” It’s an Italian adventure film following a scientist experimenting on the brains of apes. The scientist’s daughter is abducted and a search is conducted to rescue her from the apes.

Contrary to any of the prior films, the next title doesn’t try to use the “King Kong” name but is still clearly taken from its source material: The Mighty Gorga (1969). Gorga was probably the lowest budgeted adaptation of King Kong until Konga TNT. The film features monster footage from Goliath and the Dragon (1960) as a cave monster. Gorga also finds himself fighting a tyrannosaurus rex to save our main characters. The story follows the typical cliché plotline relating to a circus and trying to find the ape for exploitation only for plans to go south.

Kongticipation

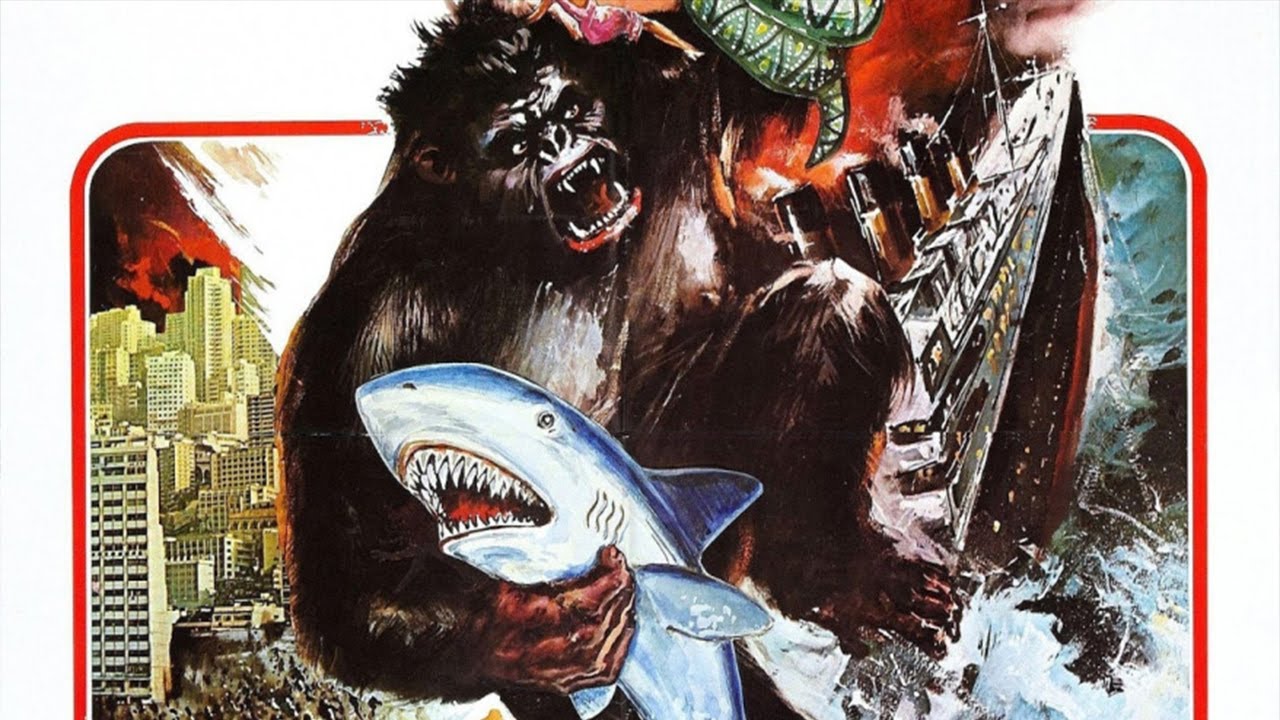

In the 1970s, people talked about the highly anticipated big-budget remake of King Kong by the famed Dino De Laurentiis (and rightly so; it won an Oscar for special effects). It became infamous for its effects and story. Around this time, there also came a wave of Kong-wannabes that have developed somewhat of a cult following as most of them fall under the “so bad, it’s good” status.

Much like in the 1960s, studios from all around the world developed their own Kongs. The first came from South Korea, the country known for its infamously awful or amazing giant monster movies. This time, an American director and cast were attached with a Korean crew behind the camera. A*P*E (1976), which actually came out two months prior to Dino De Laurentiis’ King Kong, provided evidence that the Kong formula had grown old. What many don’t understand is that the director, Paul Leder, went out of his way to create a parody—perhaps something to do with the $25,000 budget–but nonetheless, it was something more akin to Airplane! (1980).

The film features yet another poorly-made ape suit walking around open land chasing a damsel in distress. Even the alternative title for the film suggests something more comedic: Attack of the Giant Horny Gorilla. But the thing about parodies is it means the formula has run its course and has become self-aware… even if it came out prior to the 1977 King Kong film. A*P*E could be considered the original Death Kappa (2010), but instead of joking about the Japanese side of the genre, it’s humoring the Kong-tropes that had run dry. Perhaps A*P*E was ahead of its time, but nobody can deny it has become one of the greatest “so bad it’s good” films of all time with memorable scenes, like when Ape flips off the camera.

Following A*P*E, we would start to see more parodies of the famed “Eighth Wonder of the World.” December 1976 saw the release of the aptly named Queen Kong. The film is the first clear parody of the Kong tropes, this time done by a British and German crew produced by Constantine Films. Queen Kong is exactly what it sounds: a female version of King Kong in the same situations as the original. Interestingly, the film never saw a theatrical release in the United Kingdom. The reasoning was the same as with the western release of A*P*E: RKO Pictures and De Laurentiis sued the companies behind both films for infringement of the name “King Kong.” In the case of A*P*E, it would lead to a delayed release in the United States and the infamous tagline, “Not to be confused with King Kong,” whereas the outcome for Queen Kong is unknown. The film parodies both the 1977 film and the original 1933 classic with an added bit of sexual content. Was it something that may have potentially inspired De Laurentiis for the development of King Kong Lives (1986)? Probably not, but some fans liked Queen Kong over the remake. Perhaps they were on to something?

Another film went with the concept of sexualizing King Kong…King Dong released nearly a decade later. This was a full-blown pornographic film featuring a giant female ape going after a man-in-distress (or without any dress, I guess?). The film features stop-motion dinosaurs but leaves much to be desired (both figurative and literally) for viewers. The film reportedly had almost a budget of $100,000 and was shot entirely in Hawaii. Like most pornos, it hasn’t gotten much light…but that’s also due to the film having the alternative title, Lost on Adventure Island. Perhaps it would be best if the film stays lost.

Following the two parodies, the remaining films made in response to the remake were more serious—or that was the intention. The infamous Shaw Brothers attempt at King Kong released August 11, 1977. In some places the film is known as Goliathon, but most English-speaking fans know it as The Mighty Peking Man. The film features a suit by Keizo Murase (suit designer for Mothra, Gamera, King Ghidorah, Varan, and many others). Shaw Brothers was known for their kung-fu films, but they had dabbled in tokusatsu and giant monsters a few years prior with Super Infra-Man (1975), which drew heavy inspiration from Ultraman, Kamen Rider, and tokusatsu television shows of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Peking Man, unlike its predecessors, tried to stay serious, while being stylized like most Shaw Brothers films, featuring crazy stories and low budget effects.

Another attempt at cashing in on De Laurentiis’s King Kong was the illustrious Canadian/Italian co-production Yeti: Giant of the 20th Century, which follows–you guessed it!–a giant yeti as he’s chased by the military while holding a beautiful young woman in the palm of his hand. Marketed to be the next exciting film following King Kong, Yeti fell flat of that goal, but since its 1977 release, it has grown a cult following for the humor within it. Furthermore, it holds a special place in the world of giant monsters as potentially the first giant monster movie from Canada.

Two other films followed this, with one being an adaptation of the Jules Verne book Journey to the Center of the Earth, featuring a giant ape fighting dinosaurs (ironic as Godzilla vs. Kong would clearly take inspiration from Journey with the Hollow Earth). Where Time Began never saw a theatrical release in its home country of Spain, but it did see TV airtime in December 1978. A film that was in development Hell until 1987 was the indie King Kung-fu, which parodies kung-fu films and King Kong, but it doesn’t actually have a giant ape. It does feature a homage with the ape in the film climbing a Holiday Inn found around Wichita, Kansas with a person in his grasp (with some exciting stop-motion, too!).

Much like in anticipation of the 1977 King Kong, in 2005, Jackson had many people talking about his faithful remake of the 1933 movie, but this time nobody was looking to cash-in on it. Nobody except The Asylum, who’ve made mockbusters like Atlantic Rim (2013). They wanted to get some Kong action and decided to combine it with another O’Brien title, The Lost World, from which came King of The Lost World. While loosely based on the original Arthur Conan Doyle novel, it does have enough in common to be an adaptation but with a Kong twist. Unlike most of The Asylum’s work, King of The Lost World gained decent reviews, and many have cited it to be one of their best mockbusters.

King Kong vs. Kong

In the build-up to King Kong’s reintroduction in the 1970s, RKO Pictures, De Laurentiis, and the Merian C. Cooper estate all went into a lawsuit about who owned the character. This along with the lawsuit between Universal Pictures and Nintendo Entertainment over the term “Kong” would basically put the character into public domain under certain circumstances, leading to a whole swell of new Kong products.

While a bit annoying and tedious, I’ve attempted up until now to only refer to the giant ape as “King Kong” as that is the name of the character-proper. But with the rulings of these lawsuits in place, I can’t help but argue that anything under the title “Kong” is an imitator rather than the actual character. This means I would consider the recent and upcoming Legendary Pictures’ MonsterVerse features as “Kongsploitation.” Toho infamously attempted to remake King Kong vs. Godzilla various times but was unable to due to Universal, who reportedly owned the rights to the character. To keep this simple: the original story was credited to Cooper; that story was novelized prior to the film; the book fell into public domain; and because of that you can adapt the book specifically but not the movie. The name “King Kong” has some legal ownership at Universal. Unless you’re adapting the book, you can’t use it per se (which is how Disney is able to produce their upcoming streaming show). However, if you simply use “Kong” (which gets the point across), you can do whatever you wish. From this we got a whole new wave of (for the lack of better terms) “King Kong Wannabes.”

Kongimation

The first of these was in 1998 when Warner Home Video Entertainment released the animated musical, The Mighty Kong. This has become one of the most hated adaptations of the original story because it is a bright and happy story, but the tragedy is one of the most compelling aspects of the King Kong narrative. The film, while released by Warner, was actually animated across the Pacific in South Korea by Hahn Shin Corporation, so perhaps South Korea just isn’t the place for Kong adaptations? You might be wondering how this film was able to be released as it follows the original 1933 film that was still protected by copyright. The reason for this film’s existence is because it based itself off the novelization, not the film.

Warner Brothers, who purchased the RKO Pictures library years prior, clearly wants to own the King Kong character but knows they cannot. Most of the “Kong” films were distributed by Warner Brothers or are in direct conjunction with the company. The next three titles all fall under one continuity (the first time a non-King Kong branded title saw a decent life on the screen whether it was big or small). This started with the early 2000s cartoon, Kong: The Animated Series (2000-2001). Kong was trying to compete with Godzilla, who had his own cartoon, the sequel to the 1998 Roland Emmerich film from Sony Pictures. Godzilla: The Series, and people were wanting to cash in on it. Airing around the same time, Kong had two seasons that added up to forty episodes. Unlike Godzilla, the show saw life outside of the series airing on television. To capitalize on Jackson’s King Kong, a straight-to-video tie-in movie was released: Kong: King of Atlantis. If it isn’t obvious by now, this show was not faithful to its source material (once again, the original book) and included a psychic link between Kong and the main human character Jason (similar to how Nick is believed to be Zilla Junior’s father in Godzilla: The Series). Following the show’s conclusion, in 2006, the final piece to this show’s puzzle would be released straight-to-video as Kong: Return To The Jungle, a fully 3-D animated movie

Similarly, there’s the Netflix 3-D animated kids show Kong: King of the Apes (2016-2018). The show was met with poor reviews for its very childish outlook on the character. Kong is not your typical fierce monster; he’s more curious and friendly. The show is set in 2050, where three kids have to clear Kong’s name and prove that an evil person was who attacked the Alcatraz Island’s Natural History and Marine Preserve. Maybe Kong by this point has reached his late 1960s Godzilla era? To me, this show is the prime example of what can happen to a character if not regulated properly; nothing in this show beyond the inclusion of a giant ape feels like Kong. Maybe that’s a “me issue,” but not even major King Kong fans discuss this series. It’s like nobody wishes to acknowledge it. Either way, the next animated show has certainly created way more buzz.

MonsterVerse

Following the successful launch of a Godzilla trilogy by Legendary , production of an upcoming Kong film was moved from Universal Pictures to Warner Brothers in hopes of creating a new shared cinematic universe where Godzilla and Kong could collide (a rematch if you look at it a certain way). From this came the highly successful Kong: Skull Island (2017). The film is set in the same universe as Godzilla (2014) but takes place at the end of the Vietnam War. Directed by Jordan Vogt-Roberts, it shines as a glowing example of how to create a new idea for Kong. While going back to Skull Island, the film features brand new characters, a new story, and new villains for the titular Kong to fight. Even Kong feels fresh as he’s given a well-thought-out human side to his nature. The film did well in theaters (over $500 million worldwide) and was well-received by critics (a step up from Gareth Edwards’ Godzilla). This would lead us to a MonsterVerse film that would pit the king of the jungle, Kong, against the King of the Monsters, Godzilla.

In-between these two films, Warner Brothers would exploit this power of having a modern Kong CG model with no lawsuits pending for the use of the character and include him in cameo roles in both Steven Spielberg’s nostalgia-filled Ready Player One (2018) and the sequel Space Jam: A New Legacy (2021) as a side character.

To cash in on the highly anticipated fight between Godzilla and Kong, The Asylum produced the aptly named Ape vs. Monster, featuring Abraham, a Kong stand-in. The film is a combination of the 2018 live-action adaptation of an arcade game, Rampage (which took direct inspiration from Kong for one of kaiju, George the giant gorilla) and the then upcoming Godzilla vs. Kong. While the film features better computer animation than most Asylum films, the fight leaves a lot to be desired as it only lasts roughly 35 seconds (thankfully, Godzilla vs. Kong wouldn’t follow suit). Two years later, a sequel was released: Ape vs. Mecha-Ape, which could possibly be a mockbuster inspired by the finale of Godzilla vs. Kong which featured Mechagodzilla, while also being an unintentional remake of King Kong Escapes.

Originally set for a 2020 release, Godzilla vs. Kong was one of a handful of films that suffered major setbacks due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to the film being pushed back almost an entire year. Thankfully, with Warner Brothers feeling brave, the film was released March 2021 with virtually no competition, and with nothing releasing for the past year, people loved the dumb fun it was. The film brought people back to a point where they could just sit and enjoy the theatrical experience (like a theme park ride). Following the success of the colossal rematch between cinema’s biggest stars¹, a sequel was announced. It currently has the working title, Godzilla and Kong, and is slated for a March 2024 release. A Netflix 3-D animated series titled Skull Island is slated for a release soon, taking place in between the events of Kong: Skull Island and Godzilla vs. Kong.

Conclusion

You’ve basically been through “Kong 101” at this point, but this collection of films is an interesting section on the giant monster genre. Not only did the early establishment of parodies clarify that the formula for King Kong had been found, but it’s well-documented how many of these films there are. This didn’t even cover the parodies like the many references found in The Simpsons (1989-present). King Kong as a character has inspired filmmakers to try at capturing the lightning in a bottle that was found 90 years ago by Cooper, Schoedsack, and O’Brien. Even the King of the Monsters, Godzilla, was inspired by what King Kong did. Without King Kong, we wouldn’t have nearly half of cinema’s history.

King Kong came out in a time when people needed escapist entertainment to look beyond the Great Depression. While the world hasn’t seen King Kong properly in almost two decades, unlike Godzilla, King Kong doesn’t ask to appear frequently. That is what makes King Kong different from Godzilla; King Kong isn’t franchise material. He’s relevant enough in history and in the world that he can come and go as he pleases. And when he does, he only gets bigger and bigger. While Kong in the MonsterVerse may not be technically “King” Kong, it would be ignorant to not acknowledge the spike in popularity the name “Kong” has received since. And while my opinions on the 2021 film are, well, let’s say less-than-stellar, undoubtedly Kong shines through every second he’s on screen. And it shows that we relate to Kong and can feel with him and for him. So, perhaps we are the beast that beauty killed? Or maybe Carl Denham is pulling from his theatrical mind and it’s truly the beast that killed the beauty? No one can really say for sure, but one thing is for certain: Kong will live on, no matter what.