Imagine for a moment that you had a time machine. Using this miracle of technology and magic, you obtain director Jun Fukuda and screenwriter Shinichi Sekizawa from early ‘70s Japan and you show them two films: Jurassic Park and The Two Towers. Then, you give them $150 million and tell them to make a movie with Godzilla and Kong in it.

What you’d get would not likely be terribly different from Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire. (Although it would hopefully not be saddled with such an awful and unrepresentative title.)

Whether that appeals to you is going to vary quite a bit. For my part, I found the story pleasantly reminiscent of the “island” films from Fukuda and Sekizawa–Ebirah, Horror of the Deep and Son of Godzilla–complete with similar stock characters. There’s the plucky reporter who cons his way onto the voyage, the mysterious girl with a foot in two worlds, an overly-abrasive military leader, and a straight man/funny man double act of scientists. You may notice, however, that those earlier films are 90 minutes long, rather than 2 hours. Even more than Wingard’s earlier effort, Godzilla vs. Kong, the main cast’s adventure in this film seems perfunctory, almost a formality.

Where then does Wingard’s interest lie? Where does his camera point? At the film’s true star, Kong, and his sometime sparring partner Godzilla. Even as I find myself tempted to dismiss this film as yet another bit of fluff of the post-Marvel blockbuster age, I keep returning to its kaiju scenes and wondering if anything quite like them has been done before. I can only compare them to the likes of Prehistoric Planet or Walking With Dinosaurs in their length and elaborateness, filming organisms that never existed with the same earnest purpose as those documentaries filmed organisms that no longer exist. But it’s different even than that, because Kong so adroitly communicates his feelings to the audience. His journey is like something out of Conan the Barbarian, and he exudes an action-hero perfect combination of compassion, dignity, and strength. This is without any Godzilla vs. Gigan-like “cheating.” The audience is simply trusted to follow along sans dialogue, which sets the world of Kong apart from the recent Planet of the Apes films. The one time that Kong is “translated,” it’s a moment that feels thoroughly earned.

Godzilla hasn’t really changed, but he’s not meant to. This version of the beast is personally millions of years old, and resists the anthropomorphism of Fukuda’s Godzilla. Rather, his subplot is inspired by later Heisei-era films, depicting him moving through the world with mysterious, unstoppable purpose. It is, in truth, fan service–whenever the Hollow Earth plots threaten to drag, we get a cut in the nick of time to Godzilla kicking someone’s ass in a recognizable Earth locale. It’s honestly pretty smart.

It’s harder, however, to defend the film against the charge that there’s nothing underpinning the sound and fury. Sure, Kong’s and Jia’s (Kaylee Hottle) journeys to find their people obviously run in parallel, but their conclusions don’t particularly challenge the characters or the viewer. Despite yet another funding crisis, Monarch doesn’t really do much or change much, and the people of Earth are otherwise just playing spectator and helpless victim to the events. A genuinely well-acted and thoughtful exchange between Bernie Hayes (Brian Tyree Henry) and Trapper (Dan Stevens) is left hanging afterward, rather than being paid off in the final act. Much is made of Skar King’s sense of aggrievement and general nastiness, but in the film’s climax, neither he nor Godzilla are given an emotional payoff to encountering each other, despite how earnestly the human characters assured us that this was an ancient grudge match. While the theme of Godzilla King of the Monsters might seem shallow and trite if you reduce it to “don’t wreck the planet,” it’s hard to discern a message in this film deeper than “don’t be mean to cute kids.”

In my earlier review of Godzilla Minus One, I praised how that film was able to break down the technological barriers that traditionally prevented human actors and VFX-created monsters from closely interacting. Sadly, this film actually shores those barriers up. There is a distinct lack of any landmarks or features of the Hollow Earth that can be compared to both the human and digital actors, leading to the impression of parallel worlds that intersect only fleetingly. And while Wingard shows a laudable desire to change up the traditional camera angles showing kaiju moving through cities, the unfortunate result is that the cities themselves seem empty of people.

It’s a shame, too, because the final battle is a tour-de-force that adapts superhero movie fighting to kaiju fighting and improves on both in the bargain. Despite being literally weightless at times due to the exotic properties of the Hollow Earth, the kaiju retain their feeling of mass, smashing into boulders and each other with bone-crunching force. The enemies are threatening because of ruthlessness, guile, and numbers, which results in the refreshing situation that Godzilla is the most powerful being on the field by far and could still lose. A certain late-arriving kaiju steals the show with a totally unique fighting style. And as ridiculous as it feels to say this about a movie that literally has dozens of kaiju, there is a sense of restraint in the events of the finale. The main fight is kept down to a handful of recognizable players, and there is no world-ending MacGuffin like Ghidorah’s super-storm or Godzilla’s meltdown. The filmmakers correctly recognize that a bunch of angry Kongs and their “Alpha Titan” pet reaching Earth’s surface is bad enough, and that nothing else going on should be important enough to cut away from the “main event.”

Ultimately, though, we are left with something rather like most of the Transformers films. It’s a crowd-pleaser; it’s full of things that are wild and rewarding and thought-provoking for the established fans; but it’s lacking that special something for me to recommend it to everyone.

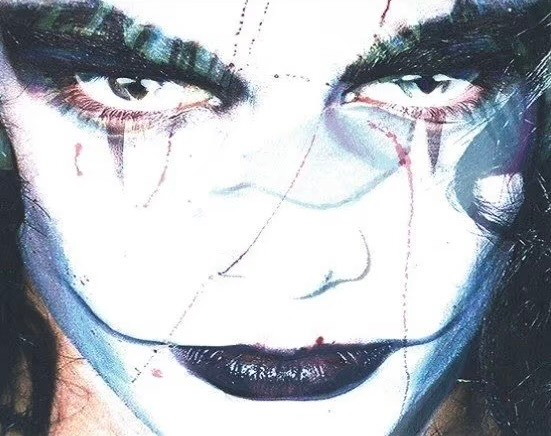

Review: Godzilla X Kong