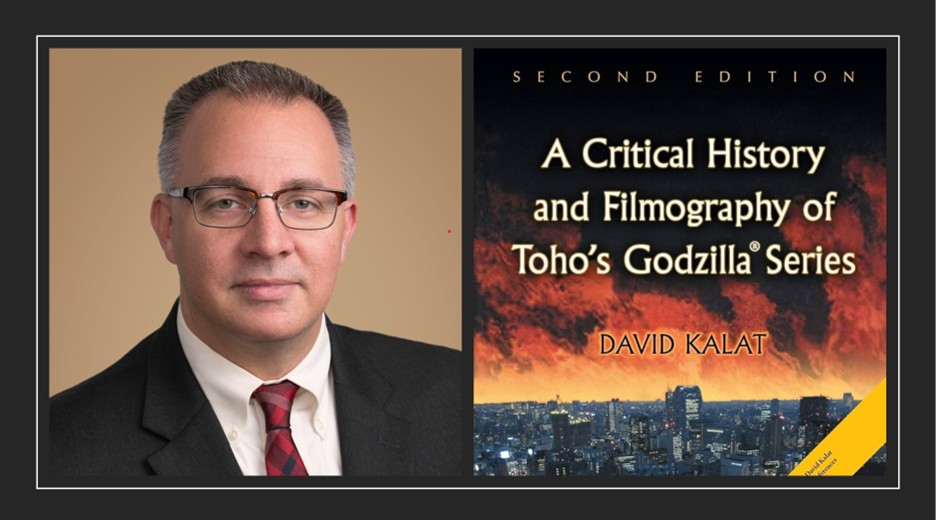

Godzilla may be a franchise of some of the most whimsical monster flick films ever made, but a closer analysis reveals the important details that keep fans of the series enticed. Kaiju scholars do the great work of digging deep into the world of Japanese kaiju cinema to explore what makes these franchises so great, and why they have such fascinating cultural importance. Recently, Kaiju United had the amazing opportunity to speak with acclaimed scholar and film historian David Kalat, author of A Critical History and Filmography of Toho’s Godzilla Series, to discuss his experiences in his work and his thoughts on the current state of the franchise.

Mario Macchiarulo: Hey Kaiju United! I am thrilled to be here with Godzilla film historian and expert David Kalat! You have rightfully earned your praise as a Godzilla scholar for your Critical History and Filmography on Toho’s Godzilla Series (1st and 2nd ed.) books, and I myself am such a large fan of your work, as it helped me appreciate Godzilla in more intellectual angles. Let’s talk about it for a bit. What were your biggest challenges creating this work? What was your research and creative process?

David Kalat: Well, thank you for those very kind and flattering words, and thank you for having me join you. It’s a pleasure to be here.

OK, so, you wanna know about the process of writing the book? Well, to be fair when talking about that process, I should note that in my mind, at least, the first and second editions are meaningfully different books. So the process of writing the first edition in the mid-1990s was characterized by my challenges in finding copies of all the movies to make sure I’d seen all of them, and gathering what information I could about their making—most of which I was sourcing from the excellent work being done in fanzines like G-Fan and Cult Movies. That first book was published in 1997, and finishes with a discussion of Godzilla vs. Destoroyah. I’d finished my writing on that book before the Tri-Star film went into production.

And then when that film came out, a couple of really interesting things happened. The first was that in the lead up to that film coming out, there was an industry-wide expectation it would be a blockbuster hit, so there were all these companies trying to find ways to cash in on Godzilla merchandising. And that created the impetus for the back catalog of classic Toho films to get released on DVD, in successively better and better editions, whereas just months earlier I’d had to travel the country scavenger hunting in video stores to scrounge up VHS copies of the 1960s and 70s era films—and had to rely on bootleggers to get any of the 90s era ones.

Then, when the film actually hit theaters and there was this wave of disappointment, the press started to orient around the angle that Tri-Star’s Godzilla was a flop. And, the easiest way as a journalist to tell that story, would be to get some Godzilla fans who could talk on the record about being disappointed by this big-budget misfire. Well, here were people like me, and JD Lees, and Stuart Galbraith, and Ed Godziszewski, and so on who had gotten things published with our names on it where we outed ourselves as Godzilla fans, and erudite ones at that.

So all of a sudden, we were getting interviewed in mainstream publications and broadcasts, talking about how great old school Godzilla films are. Like, overnight, the overall popular and critical reputation of these films got rewritten. Suddenly, our viewpoint became the established mainstream take on Godzilla.

So when I came to update my book in 2009, I realized that the widespread availability of the films meant I didn’t need to devote so much space to plot synopses, which freed up a lot of wordcount I could repurpose to exploring other ideas. I also realized that my tone in the first edition was very combative and defensive, because I felt I was litigating the case for the defense. Now, I felt like the world was increasingly coming around to my way of seeing these films—which meant I could afford to bring more of a personal and idiosyncratic touch, because I felt the stakes had lowered.

MM: You have spoken about your opinions of Shin Godzilla and Godzilla (2014) in another interview. Since then, there have been quite a few big time G films. What are your opinions on Godzilla: King of the Monsters (2019), Godzilla vs. Kong (2021), Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire (2024), and of course the Oscar winning critically acclaimed Toho’s Godzilla: Minus One (2023)?

DK: I remember back sometime before 2014, and I can’t quite pin down when this would have been but possibly around 2012, a teaser for the new Godzilla came out, and there was all this enthusiasm and buzz among the Godzilla fan community that it seemed, finally, Hollywood was gonna do this right, we were finally gonna get a proper dark and gritty Godzilla. And I remember being kind of sad about it. I’ve been very upfront about this—I fell in love with the silliest of silly Godzillas. I’m here because I saw a double feature of Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla and Godzilla vs. Megalon in 1976 at a drive-in theater when I was six years old. My love of Godzilla got baked deep into my psyche long before I had any ability to control which films I had access to, or when. You cannot get me to turn my back on silly Godzilla—that’s for me the core of this. So if Hollywood was going to take Godzilla into a dark and gritty place, I feared it was taking away the very things I wanted to see more of.

Now, mind you, I thought the Gareth Edwards Godzilla movie was terrific. I have no notes on that—it understood the assignment and is a really thrilling and exciting movie. Great stuff.

But when Godzilla King of the Monsters leaned into such bizarre, goofy ideas, with obvious inspiration from Destroy All Monsters and Final Wars, I was happy.

And the box office successes of the Monsterverse entries does indicate these are connecting to audiences in some way, even if its just empty escapism. So more power to them.

Meanwhile, you have Shin Godzilla and Minus One showing that these characters and ideas can be used to create real, weighty, impactful stories as well. So it’s the best of both worlds, really, as a Godzilla fan. As my daughter likes to say, “what a time to be alive!”

Photo courtesy of Quote Fancy

MM: Is there anything on your wishlist for the future regarding Toho’s planned financial expansion and “globalization” of Godzilla?

DK: I hope they continue to give leeway and freedom to Takashi Yamazaki to explore what he thinks is interesting. It’s a rare and special thing when you get a creator who has a real sense of personal investment in an established work of intellectual property. The Russo Brothers with Marvel, Russel T Davies with Doctor Who, Dave Filoni with Star Wars—these are individual creators with their own distinctive voices who care about their respective franchises and the results are things people enjoy watching because they feel personal while being part of an established brand. Godzilla suffered a while without that—and Yamazaki is clearly something special.

MM: What are your thoughts on the direction that Godzilla’s character has taken in the Monsterverse films? Do you think the character has been translated well for an American audience?

DK: It feels of a piece with the way that Toho has generally treated the character. That Godzilla is a sort of alpha-predator, and that means that depending on what sort of menace has showed up this time that Godzilla can either function as a threat (if Mankind has gotten too hubristic) or a savior (if some other monsters is muscling in).

MM: Godzilla has also had a resurgence in the comic world, with IDW doing unique things and Godzilla doing more pop cultural crossovers such as his run-ins with Marvel and DC’s premiere teams. Have you kept up with any Godzilla comics? If so, what are your general thoughts? Have they done well to expand Godzilla’s intertextuality and perception in America? What is being done differently from Marvel’s previous Godzilla comic run in the late 1970s?

DK: I’m sorry, I have to admit I have not kept up with modern comics iterations. But it’s funny you ask, because back in the late 1970s the Marvel comics and the Hanna-Barbera cartoon series were the only forms of Godzilla I had any reliable access to. I could get the comics at the corner convenience store, the cartoon was on every Saturday morning. So a big part of my background understanding of Godzilla was set by those American-made adaptations. And to this day my primary impression of the Seattle Space Needle is a place that S.H.I.E.L.D. had to defend from a Godzilla attack!

I’ve never seen anything that conclusively proved it, but I’ve always assumed that Toho’s ideas around the various Super X models and the idea of a G-Force were attempts to reclaim for themselves some of what Marvel was doing in those 1970s comics with S.H.I.E.L.D’s Helicarrier and the notion of a Godzilla Squad.

MM: Do you have anything specifically you would like to see in the Minus One sequel?

DK: I have to assume that they’ll introduce some other monster antagonist—that’s pretty much how this franchise has always worked. There’s a standalone film with Godzilla as the threat, then sequels where Godzilla fights other monsters. The team behind Minus One were so clever in bringing fresh new ideas to a 70-year old property, I’m at once very curious and somewhat nervous to see how they’ll handle this pivot. I’m worried my expectations could get too high.

MM: In your book, you formulate an excellent analysis of All Monsters Attack (1969). Do you think, despite its faults and heavy criticism, that it is a film that is an under the radar must-watch for fans?

DK: Wow. “Must watch” is pretty strong words.

But, I do think that film offers a fascinating glimpse into a reality about 1970s Japan that probably otherwise the cohort of people who enjoy watching Godzilla movies might miss. That’s part of what draws me to genre films, as a critic, is the way that the stuff of genre filmmaking can be used in the service of getting bigger ideas across to a wider audience.

For instance, the relatively recent Watchmen series on HBO got across big, tough ideas about the legacy of American racism to a broad, generalist audience that probably wouldn’t sit through a documentary on the same material. Personally, I had never heard of the Tulsa massacre, or Black Wall Street. Wasn’t taught in my school. But seeing that very real history, dramatized in a TV show about superheroes, taught me something about my country, my history, the real world in which I live. When I finally visited the site of the massacre in Tulsa a few years after seeing the show, I experienced that moment of history more viscerally as a result.

So, yes, All Monsters Attack is very much worth your time, especially if you realize the stuff with Gabara is nowhere near as interesting or important as trying to understand why this little kid is spending so much time in an abandoned industrial site in the first place.

Upload and Thumbnail via GORIZARD.

MM: In your Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster commentary, you explore the tonal shift in the Godzilla franchise, from nuclear horror to whimsical fantasy adventure. In what ways do you think this shift was significant for the progression of a cultural character like Godzilla?

DK: Well, frankly, there’s just only so far you can go with the dark and gritty Godzilla. That first film in 1954 works the way it does in no small part because of its cultural moment. The use of A-bombs on Japan to end World War 2 is not very far in hindsight; the testing of H-bombs on Japan just happened; the filmmakers are angry and working in a semi-documentary mode to present this metaphor to a jittery and anxious public. And, crucially, there’s widespread misinformed fear about how radiation works and what it can do. So Godzilla captures all of that, powerfully.

But you can’t really capture that lightning twice. The cultural moment fades, the shock effect of seeing something new diminishes, the anger and fear recede, and eventually the absurdity of the premise outweighs the power of the metaphor.

But—but—Eiji Tsuburaya’s effects were tremendous. So there remains an audience demand to see more of that spectacle, even as the metaphoric power of that first 1954 take on Godzilla washes away. So, yes, letting Godzilla films turn into family-oriented fun was the only way these were going to continue as a pop culture presence.

I mean, you can look at all the monster movies from the 1950s from the US, the UK, around the world, that were doing something very much like Godzilla, and how that all dried up by the 1960s. That fad passed. Godzilla endured, and endures, by stepping outside of that fad and becoming its own thing.

MM: You emphasize your belief in the American cut of Ghidorah being very strong and elaborate that these types of American cuts were almost necessary to make these kaiju films digestible and accessible to American audiences. How do you think Godzilla films’ perception in America during the era *could* have differed if these movies were never altered at all or to the significance they were altered?

DK: Right now, here in 2025, we’re in a very different place than the 1960s in terms of how American audiences interact with media. So many people now are accustomed to watching videos on their phones, where subtitles are often naturally included even in English language sources. It helps those who are watching with the sound off, it is more accessible and inclusive, and AI-generated subtitles are pretty easy to generate. Similarly, I count myself as one of those people who routinely leave subtitles on when watching TV. I’m hard of hearing, my wife doesn’t like the volume up took loud, and there’s often background noise to compensate for. That comfort with subtitles as a default has created a new audience that is so much more accepting, then, of subtitles that are needed to translate foreign language dialogue. So I think it’s hard for today’s audiences to fully understand just how resistant people were to subtitles even just a few decades ago.

What I’m getting at is that until recently, it simply was unthinkable that any Godzilla film would have been released in the US with anything other than English language dubbing. I can try to imagine some counterfactual alternate universe where that wasn’t true, but that world would be so dissimilar to the one where these movies were in fact made, it doesn’t give me much to work with to posit how the people in that fantasyland would have reacted.

So what we’re left with is that the films had to be dubbed, somehow. And Japanese grammar, syntax, and phonics are so different from English, that leaves only two options and neither is that great—either the English dialogue will track the meaning of the Japanese pretty well but be out of synch with the actors’ lips, or you can focus on good lip synch but let the content get wonky.

The thing of it is, some of the English language versions of the 1960s that were significantly altered also tended to have better quality English language tracks. Not always, it wasn’t a guarantee, but Ghidrah is a great example of an American recut that worked in favor of helping the movie.

Which is my long way around to saying that in our alternate universe where the 1960s films were shown in the US without cuts and with subtitles, I fear in that world the American audiences in the 1960s let their prejudices get the better of them and the films flopped, and without that international cash flow the series died out.

MM: What other Godzilla films would you like to do audio commentaries for?

DK: Man, I’ll yammer my way through anything. But seriously, I get a kick of coming to bat for a movie that I feel isn’t getting its due. It was such fun to do the commentary for Gamera vs. Guiron, because I dearly love that film and I enjoyed being its champion. So, yeah, Godzilla vs. Megalon. I’m up to the task.

MM: Alrighty, time for some fun questions. What is your personal favorite aspect of the Godzilla franchise?

DK: I know this isn’t what you’re asking, but my answer is how Godzilla has united me with my family over the years. So I mentioned my experience at the drive-in in 1976 already—a very specific and vivid memory of childhood and my parents. Then in 2000 I took my then two-year old daughter to see Fantasia 2000 and before it, the theater ran a preview for Godzilla 2000 (sense a theme? Movies with 2000 in the name!) and she leaned over and said “Daddy, we see that movie, OK?” And then the early 2010s when my son got super into Godzilla and we would go to G-Fest together, so he could collect Bandai toys and meet Don Frye. Throughout my life, Godzilla movies have provided a connective tissue linking me to loved ones and giving us shared joy. And they’re still making movies! More great personal memories yet to come!

Upload by GORIZARD.

MM: What are your personal favorite kaiju?

DK: Mechagodzilla. One of my very first memories of all is being 6 years old and watching in awe as one Godzilla punches another Godzilla so hard his skin tears and reveals metal underneath. That’s brilliant.

MM: What do you think are some of the most under-appreciated Godzilla films?

DK: I can’t say its under-appreciated because I know it’s beloved, and the recent Criterion Blu-Ray is just gorgeous, but I do wish I’d spent more time crowing about how awesome Godzilla vs. Biollante is. It is such a gloriously insane premise, done with such confidence. As you can tell from my answers, I’m drawn to that tension between silly Godzilla and serious. The serious Godzillas—the 1954 original, the 2014 Legendary film, Shin, Minus One—they are easy to love. They are easy to convince others to love. The truly unabashedly silly ones—like Megalon—are very very hard to love, and very very hard to convince others to love. But the ones that completely nail that razor-thin balance between both poles, that’s an extraordinary accomplishment. It’s why I love Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster so much. But Biollante—oh, man. A room full of psychic children have all drawn pictures of Godzilla attacking. A self-defense force agent decorates his office with Bandai toys. A shock horror DJ has to interrupt his punk rock show to tell serious news about Godzilla’s arrival. Scientists have a cocktail in a lounge created in the wreckage of Godzilla’s 1984 rampage, complete with his footprint now intact as a memento. The scene of Miki putting the psychic whammy on Godzilla from a helicopter platform. The scene where Biollante is first revealed in the misty lake. And all in a film about Godzilla fighting a giant monster rose!

MM: What is something that many G-Fans don’t know about the franchise and its history, but probably should?

DK: It’s been my experience that Godzilla fans are exceptionally studious consumers of information. They are very knowledgeable about the series and its surrounding context. But, if I can use this moment to shine a light on something else, I’d encourage fans to seek out a wider diet of Japanese films. Once you’ve got a foothold with watching Japanese cinema, and you are used to the sound of the language and watching subtitled fare, once you’ve figured out where to go about sourcing films that may not have wide distribution in America, then you can discover a rich and rewarding world of movies that don’t have monsters in them. I’ll single out one–Bakumatsu Taiyōden. That movie is so fabulous, so wonderful across every dimension, but it’s such an uphill battle to recommend to anyone. It’s in B&W, it’s old, it’s kind of slow paced, the title is almost impossible to properly translate into English, the premise depends on several different layers of unfamiliar culture and foreign historical context, **and** the only copy I know of requires access to a region-free Blu-Ray player to enjoy outside of the UK. Everything in that list just kills that recommendation for almost anyone… except Godzilla fans! And then I can tell you it stars Frankie Sakai, and that’ll actually mean something to you!

MM: Now for our last question, David. What is your favorite moment/scene of the franchise?

DK: I apologize in advance for my lengthy response. I know you asked that question thinking it was just a piece of fluff, but if I’m gonna answer it honestly, my answer won’t make sense out of context. So, deep breath, here we go—

Unquestionably, the single most memorable and significant scene in all of Godzilladom to me is a bit in Godzilla vs. Gigan where the Japanese Self Defense Force listen to the screams of the incoming space monsters and note gravely that one of them is Ghidorah, but the other one is unknown to them.

I’ve brought this up in nearly every kaiju-related commentary I’ve done, I talk about it my book, I am hung up on that scene. And frankly, it’s why I wrote the book in the first place.

I was watching Godzilla vs. Gigan sometime in the early 1990s—somewhere around 1992, give or take. I’d rented the VHS from Blockbuster, and it was a “new” film to me, since I hadn’t seen that particular entry before. The whole movie is tremendous fun—space aliens set up a Godzilla-themed amusement park as a plan to take over the world, and are thwarted by an aspiring comic book artist. Just perfect. Anyway, the aliens have been unmasked and they’ve revealed their dastardly plan, and they play this audio tape that’s supposed to summon the space monsters Ghidorah and Gigan to their theme park. Akira Ifukube’s music swells, the camera swoops from the statue of Godzilla in the theme park out to space… It’s ominous, and suspenseful. The space monsters appear… and then there’s that scene.

Let’s set aside the problems around the idea that playing an audio tape on Earth could effectively summon monsters from deep space to come to Earth in any amount of time that made sense as a step in some plan. Right? I’ll accept that the monsters can move through space at incredible speed. I’ll also accept they can propel themselves through space without engines or rocket fuel. That they don’t need to breathe. That they aren’t torn apart by the vacuum of space. That they don’t freeze to death. Fine, I’m with you.

It’s harder for me to accept that, while propelling themselves through the vacuum of space at unholy speed, these two are bothering to cackle and trash talk, and that the sound of their boastful cries are carried through the vacuum of space—ahead of them somehow—to be picked up by radio antennae in Japan. But, for the sake of argument, I’ll grit my teeth and go along with that too.

But it’s when the General says he recognizes the sound of one of the monsters, and not the other, that’s where the absurdity of the situation boils over. It’s too much.

Now, mind you, it’s not that I reject the film for that scene. I love it, I fell helplessly in love at that exact moment, I will never forget that moment when I saw that ridiculous scene for the first time. Because there is simply no way to take it seriously. The film cannot expect you to. The point of it has to be that it’s ridiculous—like Kermit and Fozzie allegedly being twins in The Great Muppet Caper.

And what I realized in that moment of epiphany was that this was a proper, commercial movie made by an actual movie studio that spent an enormous amount of money to make this film. Sure, compared to Destroy All Monsters or Mothra, this was a cheapie—recycling pre-existing Ifukube cues, dropping in existing special effects footage, staging monster fights on cheaper sets. But still, this was an expensive thing to make for the people that made it.

And in the 1990s, I was steeped in what people called “psychotronic films.” I went the local Psychotronic Film Society every week to basically do a live in-person sort of Mystery Science Theater where we watched bad movies and made fun of them. And all those psychotronic movies—they were cheap things made by weirdos who were allowed to let their crazed imaginations run riot because the budget was so low no one was stopping them. Ed Wood could make Plan 9 From Outer Space his way, and as result that thing is a bizarre and entrancing wreck. But Godzilla vs. Gigan was made by committee, with serious men in suits paying attention to the bottom line. It isn’t strange because some lone wolf weirdo got out of control. It’s strange on purpose. It is strange because that strangeness was part of a deliberate franchise formula.

So that got me wondering—because the obvious pop cultural parallel to 20th Century Godzilla was James Bond. Same sort of trajectory of a film franchise over roughly the same span of time, same devolution into silliness in the 1970s. But with James Bond, I could understand how it was marketing a specific fantasy. One where the UK hadn’t lost its Empire and faded, but remained an essential inflection point in the world order. A fantasy of heterosexual male power. Everything kitschy and strange about James Bond makes sense to me.

But the Godzilla franchise spent the 1960s and 70s selling Japanese audiences a vision of Japanese cities repeatedly destroyed by giant monsters. So—that’s how me in 1992, watching Godzilla vs. Gigan for the first time, that’s how I saw it. That’s what hooked me. I needed to understand **why** Japanese audiences would keep coming back for this particular fantasy of what looked to me like self-destruction, in the same way that British audiences needed to see MI6 agent 007 repeatedly save the world.

And more or less 6 years later, I published my first take on answering that question.

So, favorite scene? Gen Shimizu in uniform listening to weird squeaks on his wireless set and going, “Uh oh, some space monster I’ve never met is on its way! Better get the troops!”

MM: Thank you for sitting down with Kaiju United, Mr. Kalat. We appreciate you and thank you for your dedicated work and time. Any last thoughts or words for the fans?

DK: Oh, thank you for having me and asking such thoughtful questions! Last words? Well, every time I do a book signing, my go-to inscription is to write the chorus to the Blue Oyster Cult song— “History shows again and again how Nature points out the folly of Man—Godzilla!” And somehow that sentiment hasn’t lost any punch since I started quoting it in 1997, since they recorded it in 1977, since Ishiro Honda and friends first put these ideas on celluloid in 1954… Now as much as ever, we humans need to remember to move through this world with humility and compassion, because we’re not getting out of this alone.