Nestled in the downtown district of my hometown, Fort Wayne, Indiana, is the historic Embassy Theatre. Built in 1928 as a movie house, it’s been the host of many Broadway productions, the venue of choice for musicians and actors (such as William Shatner), and, until recently, the home of the Fort Wayne Philharmonic. But on August 24, 2025, the theatre got back to its roots by celebrating the 100th anniversary of The Lost World, the 1925 “kaiju” movie that marked the feature film debut of special effects wizard Willis O’Brien. Outside of using a time machine to transport myself back to the movie’s original theatrical run, this was the closest I’ve ever gotten to experiencing a silent film as it was originally intended to be seen.

There couldn’t be a more perfect place for me and my brother Jarod to see this cinematic classic. The Embassy is only three years younger than The Lost World, and despite many renovations, most of the theatre’s classic architecture has been maintained. The sweeping archways, warm lighting, and luxuriant carpet are a far cry from the by-the-numbers corporatized multiplexes of the present. My ten-dollar ticket got me a stub for a free popcorn. It was the fluffiest snack I’ve ever had at the movies. The auditorium is as big and open as a cathedral. It even has a balcony to give a birds-eye view of the stage (although, it’s usually relegated to cheaper “nosebleed” seats). Said stage is covered by a thick curtain. This time, a fairly large screen was behind it. On the left side was the Grande Page Pipe Organ, an ornate old-timey instrument that sat beautifully during the hour leading up to the screening. Then, it slowly descended below the stage a few minutes before showtime.

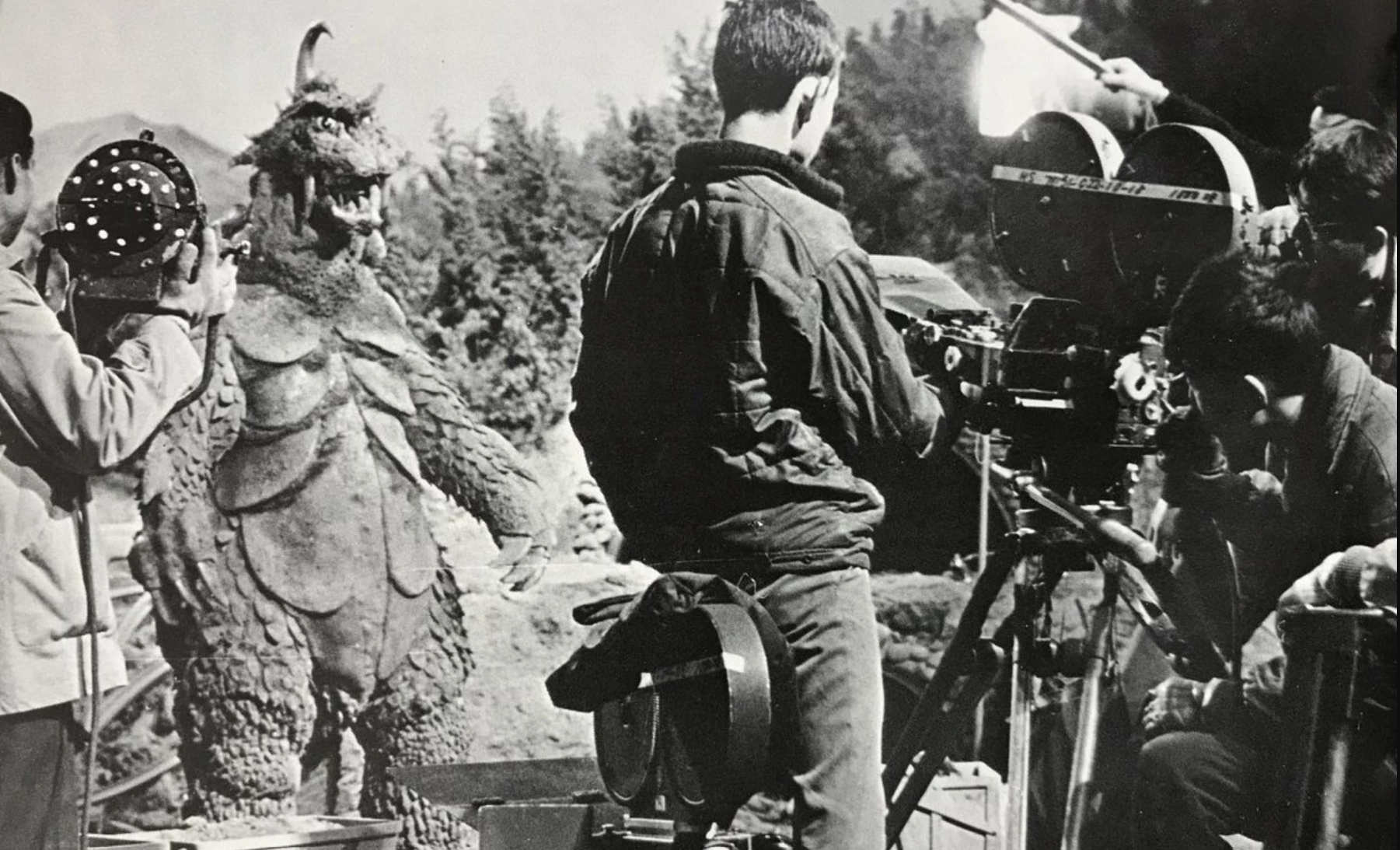

At 3pm, organ music blared from the speakers, reverberating off the walls. It immediately transported me back to a time of phonographs, swing clubs, and, most appropriately, Charlie Chaplin. Combined with the setting, all that was missing was for men in the audience to be wearing zoot suits and the women be wearing flapper dresses. The organ itself, illuminated by what almost looked like Christmas lights, rose from a trapdoor in the stage, revealing the show’s organist, Cletus Goens. After playing a fun little ditty for a few minutes, he turned to greet the audience. After introducing himself, he mentioned some background on The Lost World, including that it was the first feature film to have “claymation.” However, the details he shared were vague and, I thought, undersold The Lost World’s importance. Specifically, he didn’t mention Willis O’Brien by name, which disappointed me.

To my surprise, Goens didn’t launch into the movie. He warmed up the crowd by playing four songs on the organ. The titles of the first two escape me. (I forgot to charge my iPhone beforehand, so I had to borrow Jarod’s phone to take more photos and videos, leaving me without a means to write notes). They were pieces from the time period, if I remember correctly, and certainly helped the audience feel like they were attending a concert on the Embassy’s opening night in 1928. Sometimes music is the time machine. However, the third song he played, which he dedicated to a friend of his grandmother who was in the audience, was “Deep Purple,” a 1934 piano composition written by Peter DeRose. (Goens joked it wasn’t the baseball player Pete Rose). His last warm-up song he said took us to Hollywood, but he didn’t tell us what it was—because it was the Star Wars theme by John Williams. Hearing it be played on an organ was a new experience, and one I relished.

Video by Nathan Marchand.

Finally, the film started. A question in the back of my mind leading up to the “concert” was which cut of The Lost World would be shown. Long story short, most prints of the film were destroyed or lost after 1929, as film preservation had yet to become a priority for studios. Only truncated 50-minute prints (about five of the original 10 reels) survived for decades. However, starting in 1998, several restorations were made as more footage was discovered. This culminated in 2016 with a 2K restoration of a nearly complete 103-minute cut of the film released on blu-ray by Blackhawk Films, Lobster Films, and Flicker Alley.

It didn’t take long for me to notice that the print being shown at the Embassy wasn’t that version. First, the print still looked a little dirty. Second, it often seemed like plot points were rushed or missing. Third, the editing was choppier than I remembered; like shots or scenes were missing. Fourth, the epic volcanic eruption before the climax in London was barely a forest fire.

We were out of the theatre by 4:30pm. That was my second disappointment. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Jarod and I, being millennials, were most likely the youngest people in the auditorium. Most of the crowd were old enough to be our parents or grandparents. We didn’t see any kids. I’m not surprised, given that a film this old probably doesn’t appeal to Gen Z-ers and Gen Alphas with TikTok brain. But it should. It paved the way for King Kong (1933), which in turn created film as we know it. Regardless, the reactions from the crowd were amusing. At several points, such as the brontosaur’s iconic (and infamous?) lip curl, I heard cries of “Oh geez!” Either they hadn’t seen the movie in a long time, or they were seeing it for the first time. Abridged though the film was, this was the best way to experience it.

Until the advent of “talkies” (movies with synchronized music, sound, and speech) in 1928 with the release of The Jazz Singer, silent films required live music to be played at the theatre to create any sort of atmosphere or immersion. I sang the praises of this film’s blu-ray release, but even it had to add a music track to replicate the original theatergoing experience. Even more so than even the best “talkie” watched at home, it just isn’t the same. Seeing a silent film in 1925 was like attending a live concert: the music was played live, and each viewing could be different, depending on the location and musician who was playing.

Video by Nathan Marchand.

Goens’ music had a wide range throughout the film. Much of it was purely atmospheric, creating a mood as opposed to syncing with what was happening on screen. While “Mickey Mousing” was certainly common in the early days of cinema, the live nature of most silent film screenings at the time made that difficult in the 1920s. However, Goens did have moments of synchronized music, particularly during moments of high drama, such as the dinosaur fights. His organ playing would speed up, switch to a staccato rhythm, and/or rapidly descend as he slid his hand down the keys. It tapped into what composers like Max Steiner would do a few years after The Lost World with masterful tailor-made scores in films like King Kong (1933) while also giving the Embassy audience moments of increased immersion.

I wish I could speak as positively about a man sitting a few rows behind me and Jarod. I lifted Jarod’s phone to record a video for KU (by the way, I confirmed there were no rules against filming), and before I could hit “play,” the man sardonically said, “You gonna do that the whole movie?” Startled, I lowered the camera and simply said, “No.” I wasn’t in the mood to argue with a stranger. This forced me to position the camera at my eye line for the rest of the showing.

You might have noticed in one of my videos there’s what looks like a watermark in the bottom right corner of the screen. It says, “Activate Windows. Go to Settings to Activate Windows.” That appeared about ten minutes or so into the screening and was never corrected. It was as if a Windows update downloaded onto the computer playing the film and was notifying the user to finish installation. I eventually tuned it out, but it was a bit intrusive.

So, while it wasn’t a perfect experience, I had a good time. Getting to see such an important classic film on the big screen is not only a rare treat, it’s an even rarer treat to see a film with a score being performed live on stage. If you ever get a chance to attend something like this, seize it, especially if it’s happening in a theatre as gorgeous as the Embassy.

Next month, the Embassy’s silent film series continues with the 1925 silent version of The Phantom of the Opera, starring Lon Chaney, just in time for Halloween, with Goens once again playing the organ. I’m putting serious thought into attending. If you’re in the area, let me know. We’ll hang out and maybe record a podcast.