One of the greatest names in Japanese horror film history, Hideo Nakata revolutionized what a scary film can be with Ringu (1998) and several sequels (both in Japan and for the American remake), as well as the influential Dark Water (2002). While remembered fondly for these classics, genre fans might be forgiven for not realizing Nakata has continued making films in his chosen genre up to this day… They just haven’t quite made the same impact at home, and barely garner any notice around the world. His latest release, Stigmatized Properties: Possession (2025) for Shochiku, continues the trend by jumping on the bandwagon so successfully established by 2024’s A Strange House—but with less of the success part, but plenty of the house.

Perhaps it’s unfair to say Nakata was influenced by A Strange House; Stigmatized Properties: Possession is a sequel to the similarly-themed Stigmatized Properties from 2020, a full four years before A Strange House was released. And while Stigmatized Properties was a significant hit when it came out (as Japan’s tenth highest-grossing film in 2020 with 20.1 million yen according to Box Office Mojo), A Strange House made one and a half times as much cash as Stigmatized Properties did in 2024, punching all the way up to number seven in the top-ten box-office race. The thread connecting the films, though, is a fixation on creepy living spaces/floor plans and YouTube. Stigmatized Properties is based on the (supposedly) true stories of comedian/YouTuber Tanishi Matsubara wherein he recounts creepy encounters while living in the titular living spaces—that is to say, apartments or houses where someone died under nasty circumstances. A Strange House, meanwhile, is based on a novel (translated into English as Strange Houses) written by a fellow named Uketsu… who is a horror-themed YouTuber. The premise? A YouTuber investigates a series of evilly designed houses, each with ghastly secrets centered around ominous architectural decisions. A big part of A Strange House the film (and the book) centered around pouring over room layout documents and guessing over suspicious design choices, and while that puzzle element never comes to play in Stigmatized Properties: Possession, the influence from A Strange House is immediately apparent from the prominent (and utterly meaningless) use of floor plan documents in the posters, the pamphlet, and within the movie itself. The floor plans, though, have almost nothing to do with the plot, however.

The story goes that 29-year-old factory worker Yahiro Kuwata (played by Snow Man member Shota Watanabe in his lead-role debut) decides to quit his job and move from Fukuoka to Tokyo in order to pursue his dream to become a “talent” in the entertainment industry (a “talent” in Japan is essentially a television personality who frequently appears in various productions and roles, not limited to acting). His boss at the factory, a former actor, hooks Kuwata up with a contact in Tokyo, one Mr. Fujiyoshi (Kotaro Yoshida, a popular actor, recently of the Japanese Cube reboot/remake), who encourages the young man to try his luck at making scary videos while living in “stigmatized properties.” These properties are places where people have undergone horrific deaths—murders, suicides, grotesque accidents—and so the rent is cheap due to Japanese superstition… but also, if Kuwata can cash in by recording paranormal events while living at these places, and grow a following on YouTube, then that may also give him a leg-up in the world of celebrity talents. As Kuwata begins experiencing encounters with fearsome otherworldly phenomenon, his television career also limps across the starting line, and he meets cute and supportive Karin (newcomer Miku Hatta) at a shoot for a commercial where they play a couple. Their relationship begins as tentative friends but grows closer as the horrors Kuwata experiences (plus bouts of homelessness) escalate, complicating nearly every sphere of his life as he pursues fame through deadly ghost encounters.

My first impression of Stigmatized Properties: Possession was a profound discombobulation; I wondered if I had walked into the wrong movie showing. The movie does not start off with the sense of horror and feels more like a light drama or even a comedy. The film has an extended prologue sequence with the title card coming in late, and as I had no idea about the origins of the film going in, the aspiring talent story hit me as goofy. The goofiness is only magnified with the entrance of Mr. Fujiyoshi, whose over-the-top antics are underscored by loopy and cartoonish music every time he appears to flash his outsized grin. In the pamphlet, Yoshida claims he was trying to avoid a “horror”-ish performance and instead that he was aiming for an altogether realistic take with his acting, and while I do think his character choices lean away from a horror feel, it’s not because his character feels realistic. When the horror elements begin to come more into play, they feel serious enough, but clash a bit with some of the recurring lighthearted elements like Fujiyoshi and the absurd “ghost researcher” played by Maho Yamada (her character’s name means “god room,” which feels a little too on point). Still, by the end, that chiaroscuro of dark and light somehow feels satisfying enough—and this mix of humor and horror seems like a recent trend in films like Sadako DX (2022) and the intense whiplashing tones from House of Sayuri (2024).

One of the most interesting aspects of the film is Yahiro Kuwata, our protagonist. Critic Mark Schilling, in his review, calls him more “multilayered and humanly interesting” than the average horror-film character, and while I personally found Shota Watanabe’s performance a bit unconvincing at times, I like his bizarre perseverance in the face of the nastiness he encounters. Bear in mind, no one is forcing him to live in these haunted houses. He can move out at any time. Yet, to follow his dreams, he endures horrific encounters that even do physical damage to his body—and he doesn’t really seem to mind. After some of his bloodcurdling ghost-battles, I would think 99.9% of the human population would flee—but he comes across as mostly unfazed. This unflappability might seem overly unrealistic, but I found his chutzpah endearing despite my general distaste for many social media influencer characters in film.

The other key character is Karin, and tiny Miku Hatta is adorable in the part—which becomes more demanding as the story unfolds. In general, I found Hatta’s surprisingly generous and forgiving Karin a bit hard to understand and perhaps slightly stilted at times, and while I don’t think she lives up to the quirkiness of Fuka Koshiba in Sadako X or the disturbed Masami Nagasawa in the excellent Dollhouse (2025), for a horror debut, I thought she performs adequately.

Stigmatized Properties: Possession is structured into four episodes as Kuwata moves from one haunted living quarter to the next. The previously mentioned Schilling rightly points out that the shifting settings creates an feeling of unease and surprise for the viewer. While it can feel like a “monster-of-the-week” formula, the pseudo-anthology format keeps things fresh with the variety of ghostly fiends that appear. Usually with each new apartment/house, new characters also enter the story, though they are always very lightly sketched in and are not generally very interesting.

I don’t think that the ghostly apparitions that populate Kuwata’s living spaces (and YouTube videos) are particularly new or innovative, either. While I won’t go into spoilers yet, each ghost mostly follows very familiar Japanese ghost story tropes, sometimes even seemingly aping Ringu and Ju-On but with less lethality (the show IS based on Matsubara’s YouTube program and sundry collected published stories, and I can guarantee those “ghosts” on his channel kill anyone—really, he mostly seems to just intone creepy anecdotes at the camera). There is an ultimate through-line that wraps up much of the action at the end and creates a sense of catharsis (without the sense of doom that many Japanese horrors end in), though even with that convenient narrative structure, there isn’t always a sense that each story is concluded so much as Kuwata simply moves on.

Outside of simply being cliché, the ghosts in Stigmatized Properties: Possession feel somewhat generic and cheap in execution as well. Here we are beginning to move into spoiler territory, so here’s my warning—I am going to discuss the ghosts now in some detail. If you skip past this next paragraph, you’ll be back in a spoiler free zone.

SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS

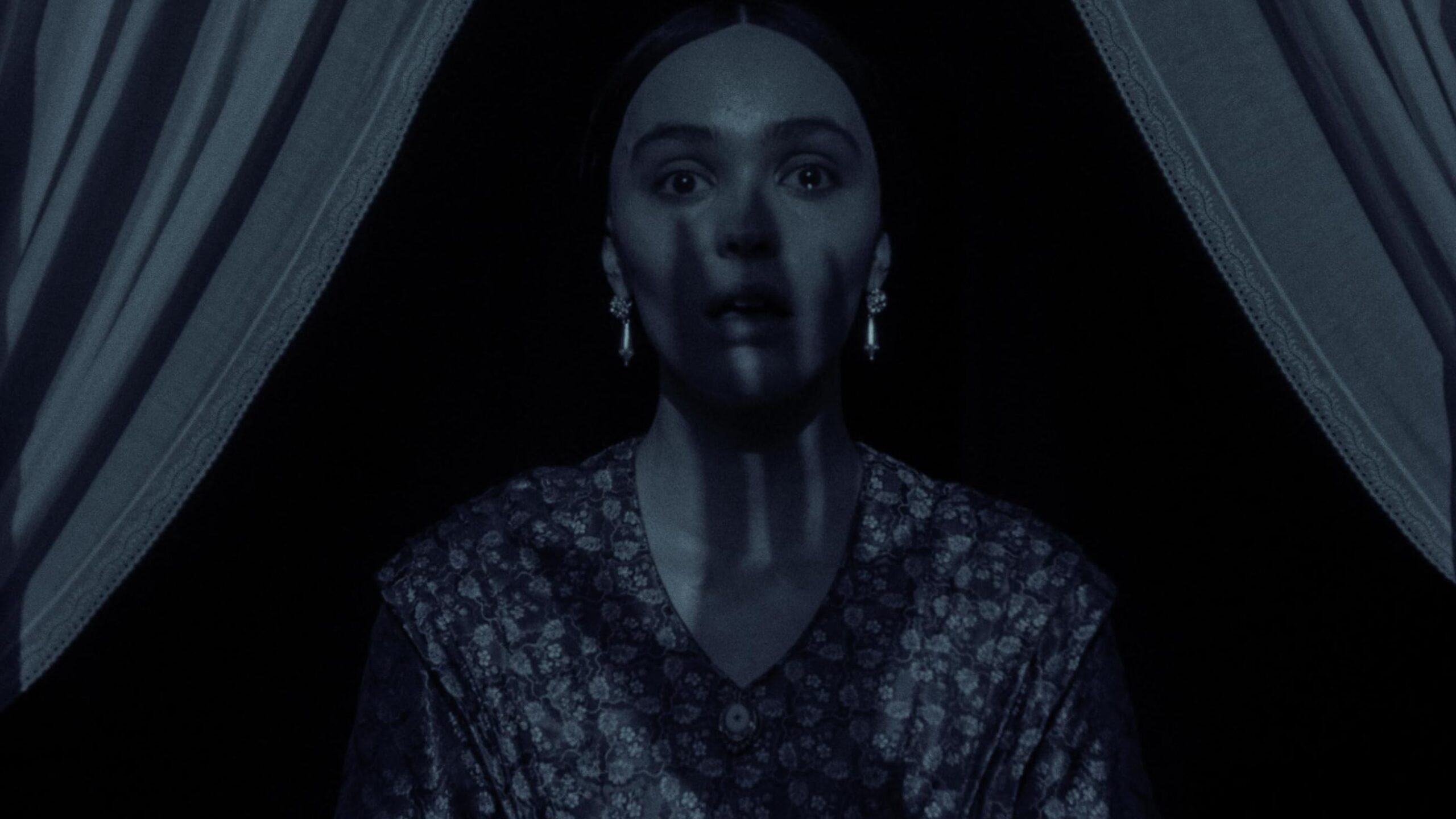

Basically, the first ghost is a pretty standard Sadako or Kayako clone—an onryo with broken fingernails, long black hair that gets everywhere, and the usual close-ups on her ugly oculars. She is the first ghost to appear (and her trademark is a missing eye, which at least marks her as somewhat unique), but she largely looks like any bog-standard wet-dead Japanese ghost lady. She is followed by a ghostly little girl inhabiting a ryokan (director Nakata wanted this old-fashioned building to appear as a place for worship, which adds a certain odd solemnity to the setting) where Kuwata is filming, and she is—if anything—even more generic. We get the usual glimpses of the murdered child running through halls, the creepy voices over the sound equipment—the most horrific bit with her is an admittedly unnerving murder sequence where viewers must endure watching the child get smothered to death by her wretched mother, all while the child pounds on the floor. Despite myself, when the mother catches a glimpse of Kuwata watching her and lurches forward with fierce eyes, I flinched a little inside.

The third haunted setting is the “Forest House” share-house, in which Kuwata begins living with two young men around his age. The idea of this setting, again as described in the pamphlet, is that the creators wanted to put together a setting drastically different—not the rotting apartment with fingernails broken off in the tatami like the first, nor the solemn religious ryokan, but a comparatively lived-in and cheerful housing establishment where one would not expect horrific goings on. The ghost here is an old bag who leaps out of the shadows onto someone’s back (for me recalling Natre from Shutter [2004]), and we get a quick look at her gnarled face. I found her risible, but the resulting carnage (and the actions of the black cat) create a hideous scene. The final ghost is a huge surprise (though there are hints scattered throughout the movie).

The biggest spoiler, of course, comes with the last stigmatized property, which is Karin’s apartment… and Fujiyoshi’s apartment. After Karin and Yahiro begin living together (actress Hatta describes the scene where she invites Yahiro to come to her house as very difficult and the sequence that left the biggest impression on her because she realized that it felt as if she had an ulterior motive despite the character’s purity, and the sequence becomes more meaningful when she realized that everything was orchestrated by Fujiyoshi). As it turns out, Karin is not her real name—it’s Riho, and Fujiyoshi is her father who went to jail after accidentally killing Riho’s stepfather. Riho changed her name to escape her past and the stigmas that followed her around, and at the climax we learn that Fujiyoshi is dead and that his ghost has been guiding Yahiro all along. Riho and Yahiro visit Fujiyoshi’s trashed apartment and see his corpse (the design crew put a lot of effort into sculpting the dead body to appear significantly rotted away while retaining actor Yoshida’s distinct features. I personally found its appearance a bit unconvincing perhaps because of these two competing goals, but I think that uncanny quality may work in the movie’s favor.

In a comment from the film’s scriptwriter, Daisuke Hosaka (famed for his terror village trilogy), the writer expressed a desire that with this story, he wanted to explore whether even a ghost might be able to bring solace to a person, and that if he could bring about even a small sense of kindness within the terror in the story, that would be his greatest joy as a scriptwriter. One might argue that the effect is a little cheesy, but it’s there—the kindness sparkles through the fear at the end partially in that uncanny corpse and the kind smiles of Fujiyoshi as he guides his daughter to healing, and I kind of want that sense of hope in these crazy times.

What all the above have to do with the writing of Tanishi Matsubara and his supposed encounters with ghosts via living in the titular stigmatized properties feels unsubstantial. Just like with director Hideo Nakata’s sci-fi-horror It’s in the Woods (2022) which ALSO was supposedly based on real events, we get a glimpse at some vague imagery over the credits of the “actual” YouTube shots that inspired some of the madness in the movie. In the pamphlet for the film, we even get a side-by-side comparison of Matsubara’s wounded neck (which supposedly came from a ghost encounter) and the bite Yahiro sustains from the first spirit of the movie, deliberately placed in the same area where Matsubara was injured. The problem is, it’s hard to even see Matsubara’s “wound,” which looks like he might have just scratched himself a little too vigorously in the middle of the night. For as successful as Matsubara’s books and YouTube videos may be, I personally hold “true ghost story hunter” content like his in pretty low regard because it feels like such blatant chicanery (much like the entire Conjuring franchise as it is based on the highly questionable escapades of Ed and Lorraine Warren), and so the film feels less impactful as a result.

END SPOILERS

When I went into Stigmatized Properties: Possession, I had very low expectations. Reviews I had seen online were not enthusiastic, and the poster looked cheap as well. At first, I thought my expectations were coming to a depressing reality—I whispered to myself towards the end of the first episodic encounter “this is trash.” Yet, after working through all four ghost tales, and experiencing the careful unraveling of the central mysteries and touching character moments, plus the oddball resilience of Yahiro as he finds his niche in life, I found the heart-warming center beneath the warmed-over spectral cliches a surprisingly compelling mixture when the credits played over an enthusiastic idol bopper. Sure, I’m not completely obsessed with this sequel, but it doesn’t deserve any major stigma.

Overall score: 6/10

Stigmatized Properties: Possession provides a mixed bag with several genuine creepy moments and a thick-skinned protagonist, but doesn’t completely overcome cliched and often silly supernatural shenanigans.

Stigmatized Properties: Possession was released on July 25, 2025 in cinemas in Japan. Review is based on the Japanese release.