In 2005, Koji Shiraishi (known later for films such as Carved & Sadako vs Kayako) released the film Noroi ノロイ, known internationally as Noroi: The Curse, to Japanese cinemas and would be met with a positive critical reception from Japanese film critics for its excellent usage of the found footage format that had since been revitalized with the 1999 film The Blair Witch Project (Daniel Myrick, Eduardo Sanchez). Further praise went to the acting talents of Jin Muraki, Marika Matsumoto, & Satoru Jitsunashi for selling the raw reality of the film in which it is set. But why is this film so beloved? Why, when so many other found footage films falter, does Noroi succeed? Why is this film highly regarded on domestic and international shores as one of the very greats of the horror genre?

To first understand Shiraishi’s vision, let us discuss the “found footage” element of the film’s narrative. The usage is really superficial in retrospect, given that the film’s true form is a mockumentary. You may be asking yourself, “What is a mockumentary?” According to Dictionary.com, a mockumentary is defined as “a movie or television show depicting fictional events in a documentary-like presentation,”a term officially coined by Rob Reiner, who directed a little film in 1984 called This is Spinal Tap.

While Noroi may not be grouped as such under Wikipedia, or maybe someone with a basic understanding of filmmaking, mockumentary is a much more apt description for it, despite having those obvious found footage aspects from Kobayashi and his cameraman, due to it having footage spread across television shows, news reels, live performances, and videotapes. This aspect also applies to the fact that the film is a documentary about Kobayashi, a journalist known for writing about real-life horror and tragedies with many novels and articles to his name (which, in the film’s promotional material, was given websites as a mockup, almost making the whole movie as believable as possible). These written works describe folklore left to rot in the collective consciousness as we move further away from the traditions that prevented some of these beings from wreaking havoc on the mortal realm.

Simultaneously, to give the film an almost science-fiction edge, the introduction of people with ESP abilities, able to see and hear beings and objects from beyond the visible eyes, with these ectoplasmic worms that are all about the walls and streets of Japan, surrounding those with ESP abilities, or perhaps surrounding all things. The film leaves the idea to the viewer to decide whether it is something that only surrounds those with a sixth sense or whether it may surround our entire universe. Hori-san says that it can consume people with ESP like a disease, yet it isn’t really explained what that means or entails for someone with such abilities. Perhaps that really is the unanswerable question: like karma, it is about whether someone is just that unlucky — or not; it is entirely up to how we interpret such things.

The way the film introduces the ESP is clever. It’s initially presented through a Japanese game show of sorts, showcasing these children with this ability in a room and asking them to see if they view what the man sees in the kaleidoscope. Some pull up with unique shapes, but not the one that he sees, until one girl (Kana) shows the exact same shape that he saw on the paper, which makes her family a deal of sorts. Soon, she befriends (off-screen) Hori, an ESP conspiracy nut who lives in a room with tinfoil spread everywhere to block out exterior noise (very much an archetype of the looney sage who sees what others can’t, but in a sense, reality does have those types).

The film’s way of further grasping the reality of the world is by having actors and creators play fictionalized versions of themselves, as if this is genuinely just part of their everyday lives. This element is none more prominent than in Marika Matsumoto. She plays herself in a main role as an actor who is initially brought along by Yoshiaki Yamane & Takushi Tanaka for their Unigirls series to explore the remains of the shrine where the demon was once worshiped. Sure enough, the demon begins in part corrupting Matsumoto by making her convulse and wail in pain or start audibly groaning as if she is in terrible pain.

Noroi plays this totally straight, yet, in that sense, it becomes so grimly real as she sells the genuine terror and fear that comes from what feels like a person really becoming overcome with this supernatural force. It seems afterward that whoever Matsumoto and Kobayashi come into contact with is roped into the curse as if they are spreading it by the sheer sight of their eyes. The film takes a turn from this point and gradually becomes increasingly overbearing and unsettling. It’s as if you are watching something that was meant to be left on the cutting-room floor. One moment you hear and see Matsumoto being overtaken by this curse, to seeing innocent people like her upstairs neighbor or members of a care-taking education club be victims of a public hanging, they commit themselves under the curse’s affliction.

The audience doesn’t see these people after you initially meet them again on screen. Yet, the fact that they come back and are killed off in an off-screen fashion that feels so shocking and frightening shows that even just telling you and not showing you through methods like papers, photography, and news reports is enough to make you feel your body melt from the anxiety-inducing threads of events that wove into this feeling of dread. A great film draws you in this way, by luring you into its embrace to reward you for the small details you notice and for letting your own personal feelings attach you to its work. So when a film like this rewards you for paying attention to the faces and names of these interviewees and seeing it come back in a shocking way allows to feel like you didn’t just hear these random names but these people who have a name, a face, a voice, and a life attached to them that just got torn away from them because of the Kagutaba’s curse.

So how do we find the source? Through Kobayashi’s remembrance of the family of two next door at the start of the movie, he embarks on a journey to the original village that housed the original exorcism that was holding the Kagutaba down from entering the mortal realm in its malevolent rage. He discovers through an old man who used to know people from the village about the exorcism ritual and what happened when the final ritual was committed: the mother Junko was a descendant of the priestesses who were used as the hosts in the ritual to cast it away. However, it went horribly wrong when it was her time to host it.

Junko is found bitter, lonesome, and destroyed at her home, with dogs littering the houses on the street, with no signs of the child she took in. Kobayashi isn’t able to make much sound out of her, so he explores the town that exists out of the former villagers after the Japanese government built a dam that drowned the village to discover that there are sickles on every house as a remnant of the old tradition that wards off the spirits and demons. Later, he learns that Junko had worked at the nursing school and had in reality stolen fetuses and forced abortions in what seemed to be the exorcism to pass the Kagutaba into a new host body and that the head of the nursing school was found hung in the park (mentioned previously in paragraph 2) afterward as if Junko had left a curse on her to die as a sacrifice to the eventual rise of the demon again.

Matsumoto and Kobayashi decide it is time to once and for all put the demon through the ritual to maybe end the curse, so Hori is brought along as he desires more than anything to kill the Kagutaba and hopefully find out what happened to Kana-chan, as he believed the ESP worms consumed her. The initial exorcism seems to go right, but Hori suddenly begins freaking out and runs out into the forest where one of the temples of the Kagutaba resides, screaming that they have to get out as fast as they can, while he finds Kana in hysterics. Kobayashi gives chase, and the movie begins really cuing us into the fact that we didn’t solve anything and that the demon has one last trick up its sleeve.

So when Kobayashi chases after Hori, he discovers several dead dogs from the town stripped of their skin and a magic circle enclosing them, as Hori warns Kobayashi to stay away before he disappears to leave Kobayashi confused and filming the events that unfold. Then, Kobayashi spots Hori in a vegetative state near the ruined temple and flips on his secondary lens to see that these worms are consuming Kana that take on the shape of these fetuses, slowly feeding on her as they slowly reach their way toward him.

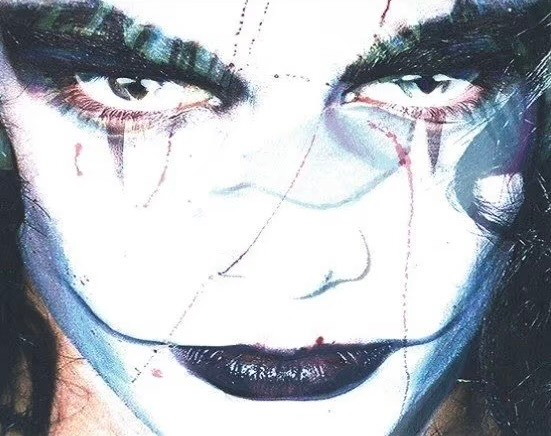

Cut! The movie hits you with this jaw-dropping scene that leaves you utterly speechless and with a sour feeling in your stomach as you watch Kana be consumed and Hori at the mercy of these worms all the meanwhile we see Matsumoto become overtaken by the demon again by wheezing and groaning, then running hysterically into the forest in possession and screaming at the top of her lungs before ending collapsed by the river as the cameraman tries to snap her out of the state and it fades to black. In just this set of events, does it feel like the curse will never end, despite how uneasily it felt like everything was lifted when they performed a mock exorcism over the lake? Could it be over?

It could easily end here, but we know very well it cannot, and so we flash forward to thinking everything is fine. However, Kobayashi thinks about how Junko is still out there, and Kana & the boy Junko took could still be alive. So, he embarks back to her place and in this moment does Shiraishi’s film wrap itself around you in a total shock as we find out the fetuses were used for the ritual, Junko has hung herself, Kana is dead by a table, and the child Junko adopted is left alive by Kana’s side, muted and seemingly lost. The film is further lowering your guard, playing with you to think that it is all over, and yet we still have more time to unleash one last treat upon your eyes, or pain, depending on how you view it.

Flash forward, Kobyashi has adopted the child into his household, and he seems to be doing quite well for himself. He is eating at the table with him and his wife, but suddenly Hori bursts in screaming that Kagutaba is not dead and that the boy is the new host of the demon. In a desperate attempt, Hori begins assaulting the child as Kobayashi and his wife try to stop him and temporarily knock him out, but not before the camera he films flashes on the busted head of his adopted son in the face of the Kagutaba’s image. Hori and his wife begin to be taken over by its influence. Hori and the child, in a muted trance, slowly walk out of the house. Kobayashi’s wife douses herself in gasoline and lights herself aflame, which burns the entire house down, and Kobayashi’s whereabouts are left alone– yet soon after, Hori is discovered crushed in a vent in a horrific state that is hard to see even on a paper clipping.

Shiraishi has hit you with his final play to leave you with one last frightening hook that the demon is now out there, living in a child, and can cause more pain and suffering for all, while you sit agape and uncomfortable as all sin. This is the masterclass of work that Shiraishi has given you, a film that burns itself into your memories with not a lick of forgettable moments in its wake. You are part of the message now, you feel its dread consumes you as you want others to see what feels incredibly forbidden to see. Noroi is a movie that will leave you afraid, uneasy, and anxious, and that is the mark of an effective film: feeling.

Noroi is available to stream on the following platforms:

Apple TV, AMC+, Arrow, YouTube, Google Play, Amazon Prime Video, Fandango at Home, Shudder, Hoopla, and Philo.

Noroi is available on Blu-ray (US/UK) from Arrow Video as part of the box set “J-Horror Rising.”