GODZILLA VS. THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA

(PART I of II)

The unlikely connection between the King of the Monsters and the Angel of Music.

2025 marks the 100th anniversary of Universal Picture’s gothic horror classic, THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA. Released in 1925, the film starred Lon Chaney Sr., dubbed in the press as “The Man of a Thousand Faces,” in the title role. For context, Chaney was the Gary Oldman of the silent era, pioneering special effects make-up he created in his various roles. PHANTOM is arguably one of the actor’s most famous roles, but others include THE HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE-DAME (1923) and the lost film LONDON AFTER MIDNIGHT (1927). Just in time for Halloween, Kaiju United looks back at the film’s original source material for a peculiar connection to one of cinema’s “biggest” stars… GODZILLA!

VOICE OF AN ANGEL, CRY OF A GOD

1925’s PHANTOM Of THE OPERA was based on a 1910 novel (serialized in newspapers in 1911) by avid fan of SHERLOCK HOLMES and French journalist, Gaston Leroux. In one of the earliest examples of “found footage,” the novel details Leroux’s investigation into a series of mysterious events that occurred at the Charles Garnier Paris Opera House. Occurrences that were attributed to a ghost.

SPOILER ALERT: Leroux discovers that a lot of these foul deeds were not the cause of some haunting, but done by a man manipulating and frightening the staff by pretending to be a spectre. A man named Erik who, deformed at birth, fell in love with a beautiful Swedish soprano named Christine Daae. Erik was responsible for several murders in the hopes of elevating Christine’s career and protecting his anonymity.

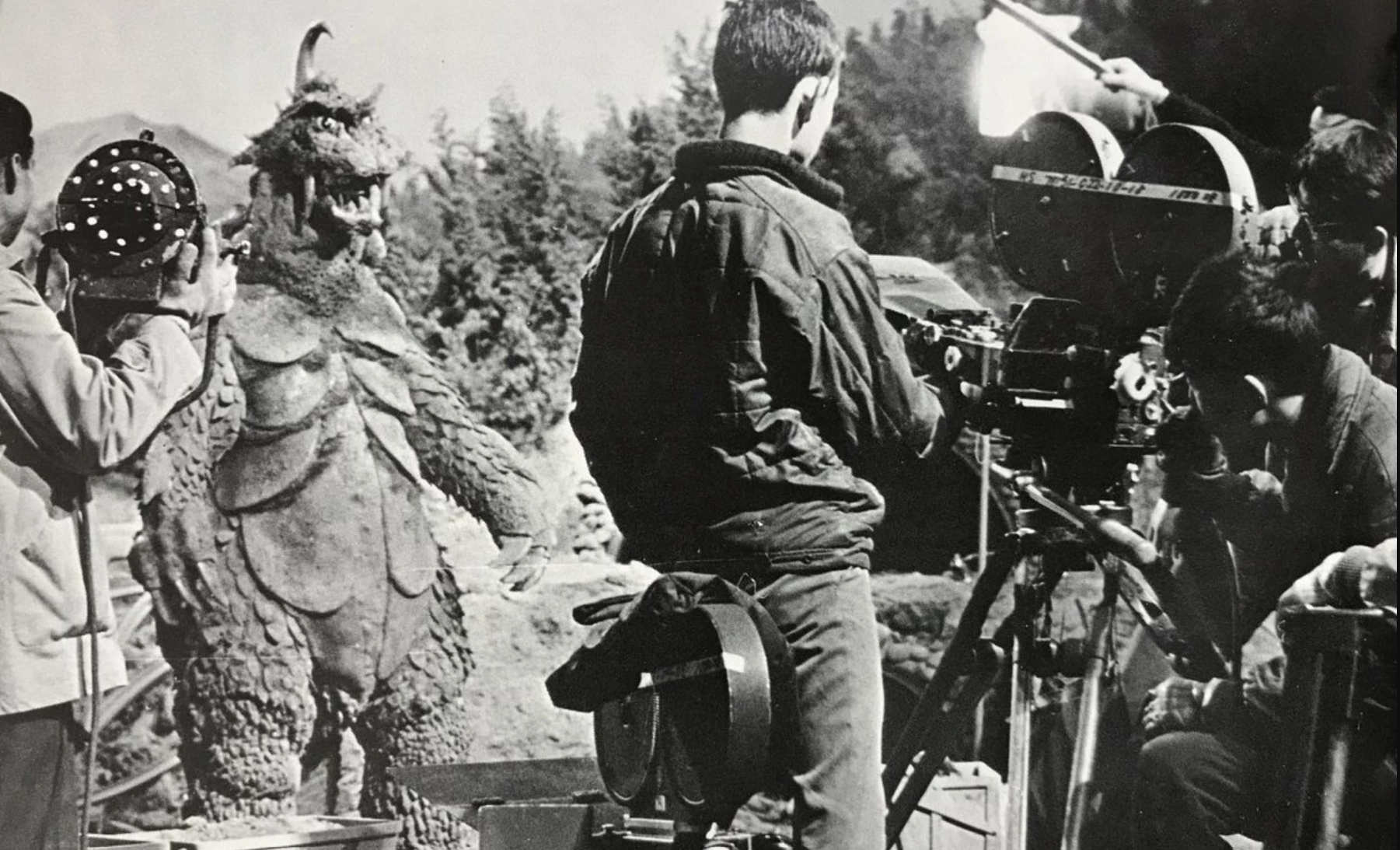

In regard to Godzilla, a certain detail towards the end of the novel reveals an unlikely connection to one of the giant monster’s trademark characteristics. By now, it’s no secret among die-hard Godzilla fans that the creature’s distinct roar was created by the film’s composer Akira Ifukube. When the original GODZILLA (GOJIRA) was in production, the filmmakers tried a variety of animal sounds for the monster. But none had the mysterious factor they were looking for that signified the gargantuan. Born on May 31st, 1914, in Kushiro, Japan, Ifukube was a musician who decided to become a composer at the age of 14. He studied forestry at the secondary school in Sapporo while composing in his spare time. He achieved the monster’s signature roar by loosening the strings of a contrabass (double bass) and rubbing the strings with a resin coated glove. The effect was recorded and manipulated in various ways by experimenting with different pitches, reverbs, and speeds, ultimately resulting in the iconic roar we know and love today.

This same effect is mentioned in Chapter 24: “Barrels! Barrels!” of the original PHANTOM OF THE OPERA novel by Gaston Leroux, though the novel predates GODZILLA by 44 years. After Christine Daae is kidnapped and taken to the Phantom’s underground layer, her lover Raoul and a mysterious Persian detective are in pursuit to rescue her. Five cellars below the opera house, their attempts lead them to the discovery of a mysterious underground lake, various catacombs, passageways, and an array of torture chambers constructed by Erik, the Phantom. It is in these torture chambers that our heroes inadvertently find themselves trapped.

One particular torture chamber causes its victims to slowly die of heat among a maze of mirrors, adorned with a single faux palm tree in the middle of the room constructed out of sharp metal. The tree is reflected among the mirrors to give the illusion of a room lush with vegetation. As our protagonists are slowly being suffocated to death, Raoul claims to hear the roar of a lion getting closer. Fearing there is a beast caged in the next room waiting to pounce, The Persian assures Raoul it is just another illusion and explains how Erik was able to imitate the growl of a lion using catgut (used for strings on musical instruments such as violins) and rubbing those strings on a musical instrument with a resin coated glove. The following is an excerpt from the Barnes and Noble edition of the novel where The Persian character is explaining the method to the story’s protagonist Raoul:

“These effects were easily obtained; and I explained to M. de Chagny how Erik imitated the roar of a lion on a long tabour or trimbrel, with an ass’s skin at one end. Over this skin he tied a string of catgut, which was fastened at the middle to another similar string passing through the whole length at the tabour. Erik had only to rub this string with a glove smeared with resin and, according to the manner in which he rubbed it, he imitated to perfection the voice of a lion…”

It’s also important to note that while the original Godzilla roar stemmed from a contrabass, the early Hesei era Godzilla films and some of the Millennium films, did include manipulated lion growls to trail off the foreboding sound effect.

This strange alignment now leaves readers with several unanswered questions: Did Ifukube ever read the novel? Was the novel even accessible in postwar Japan? Was Ifukube even aware of the story? Was it merely coincidence? How did Ifukube come up with this similar idea to use a resin coated glove for Godzilla’s roar? If not the novel as the source, then what was the inspiration that sparked this idea? It is amusing that both The Phantom and Ifukube used similar procedures to really drive home the presence of large living creatures.

Obviously, Gaston Leroux had to have known, or witnessed, someone achieving this effect which only adds to the story’s already many anecdotes of truth attributed to it. According to a descendant of the author, a good portion of the story is, in fact, based on true events!

TRUTH IS STRANGER THAN FICTION

Writers often use elements from real life to base their stories, and The PHANTOM OF THE OPERA is no exception. Much like Bram Stoker having DRACULA haunt places from the Count’s Transylvanian castle to Whitby, England; or Victor Hugo’s hunchbacked Quasimodo residing in the, still standing, Notre-Dame de Paris Cathedral, Leroux’s gothic tale is probably the one out of the bunch that is the most factually based. Or, at least partially inspired by actual events.

Veronique Leroux, whose family owns the Chez-Leroux café, adorned with all things Phantom related, is the great granddaughter of Gaston Leroux. She and other members of her family have stated that 75% of the story is true! There have also been claims that, while on his death bed, Gaston Leroux confessed that the entire story was true. The novel is certainly written in a manner as if it was. Like the previously mentioned Notre-Dame, the story has an air of verisimilitude in that it occurs at a location people can still visit, the Palais Garnier Opera House in Paris.

Of the actual events that took place: On May 20th, 1896, due simply to “wear and tear” a counter weight for the massive chandelier in the opera house did fall into the audience, crushing a woman and injuring several others. Several characters in the novel actually DID exist or their names were inspired by real life counter parts. The object of the Phantom’s affection, Swedish soprano Christine Daae, is based on a Swedish opera singer named Kristina Nilsson. The underground lake DOES in fact exist! A branch of the Seine was discovered when building the foundation, but sadly, the lake is unfortunately inaccessible to the public as it is still in use to maintain and fluctuate water levels. The most shocking element pertaining to the story’s veracity, however, is an account of a pianist who was obsessed with a ballet dancer. A fire had ensued in the opera house, and the ballet dancer had died while the pianist was disfigured from his injuries. Overcome with grief and resulting in madness, there were stories that when the building was being repaired, he would sleep in certain areas overnight.

While Erik was born with his facial deformity; a victim of his era enduring a lifetime of abuse, many filmmakers have opted to go with a less complex backstory reducing it to a simplified revenge plot. Perhaps this story of the pianist who went mad was the inspiration for future alternative storylines?

Readers can now listen to one of the most accurately translated adaptations in the form of an audio drama on Spotify entitled A GHOST IN THE OPERA HOUSE, which faithfully translates Leroux’s original 1909 text.

Co-writer Clark Wren had this to say about Erik using the same method as Godzilla’s roar, “It’s the first time the Phantom’s genius as both musician and acoustician collides with his monstrous persona.” Wren adds, “What Ifukube did for Godzilla – dragging the resin coated glove across the strings – Erik turn physics into fear. Both monsters weaponize vibration: the resonance of sound as power, as territory, as identity.”

Historian & Co-writer Josep Farkas further elaborates, “It’s not random at all. Erik imitating the roar is a study in acoustic illusion. He’s using the chamber’s architecture as a resonator, precisely the kind of experimentation Akira Ifukube later used on Godzilla’s roar. It marks the earliest literary depictions of ‘sonic engineering’ as character psychology.”

Actor Alexiel Ravenswood who voices the Phantom in the audio drama explains, “Both Erik and Godzilla use sound as a boundary.” A roar that says, ‘I exist and you cannot control me.’ It’s remarkable that in 1910, Leroux imagined that idea so vividly he anticipated the vocabulary of modern monster cinema. The same artistic gesture separated by half a century.”

In addition to the audio drama, an upcoming graphic novel adaptation of Phantom of the Opera by Legendary Comics, the same Legendary responsible for the American Warner Bros. “Monsterverse” Godzilla films, is currently in the works. In the second part of this article, we’ll be diving into Legendary’s upcoming graphic novel done in collaboration with Ron Chaney, the great grandson of Lon Chaney Sr. Also, a possible mystery may be solved regarding an un-made Godzilla film! Stay tuned!

For more information on the family-run Gaston Leroux Café, you can visit both: https://www.chez-gaston-leroux.com/ and on Instagram @chez_gaston_leroux.

The audio drama, entitled A GHOST IN THE OPERA HOUSE translates Leroux’s original 1909 text and can be heard here: