The year was 1963. Eiji Tsuburaya had broken off his exclusive partnership with Toho Studios (e.g., Godzilla, Eagle of the Pacific, Mothra, etc.) and had begun his own company, Tsuburaya Productions. The journey to come would culminate in staging the production of two of the most important tokusatsu shows in Japanese television history.

Originally, Tsuburaya wanted to launch his new studio with a show comparable to American offerings such as The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits; a science fiction anthology show like the aforementioned western counterparts. Tsuburaya, and his partner, producer/director Toshihiro Ijima, went even further with this influence — the original plans were to present a Rod Serling-type host at the beginning of each episode!

However, The Tokyo Broadcast Station (TBS) conducted a poll, and results revealed that kaiju were just too big to ignore with native audiences. Creatures in the same style of Godzilla, and his brand-new rival, Gamera, were pushed to the forefront of the proposed broadcasts. Of course, this ultimately made the monsters centerpieces, capitalizing on the massive popularity of kaiju eiga continuing into the late 1960’s.

Regarding the “Rod Serling type” mentioned above, the on-camera host concept was replaced by a voiceover narrator each episode, telling viewers (especially in Episode 9, “Baron Spider”) that “For the next 30 minutes, your eyes will leave your body, as you enter this mysterious time.”, as well as comments about “The Unbalanced Zone” sprinkled throughout. Another adjacent television show, BBC’s Quatermass, is brought up in the “influence” conversation in The Q Files by Jim Cirronella and Kevin Grays. Personally, it is indeed a compelling coincidence to have such a show have that kind of narration, using of the term “unbalanced zone”, and not have any influence from the American shows that inspired the original concept. Either one of the three mentioned shows above could be argued as an influence, in this writer’s opinion. An unrelated comparison to this discussion would be the comparison of Lady Snowblood AND Female Prisoner Scorpion as the influence behind Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill.

Finishing the initial concept, the next step for TsuPro was the development of its title. The original working title, Unbalanced, was later changed to the now familiar Ultra Q. The name Ultra Q reportedly came from the Japanese gymnastics team , who used what was called an Ultra C plan in their routine during the 1964 Olympic Games. The phrase Ultra itself was beginning to gain popularity in their country’s youth culture at the time, as well. The Q aspect meant Question, thus making the full title Ultra Question. What is the Ultra Question? Perhaps it’s the name-dropped “unbalanced zone”. Interestingly, it also serves as a reference to Obake no Q-Tarō, an animated series based on the manga of the same name by acclaimed author duo Fujiko Fujio.

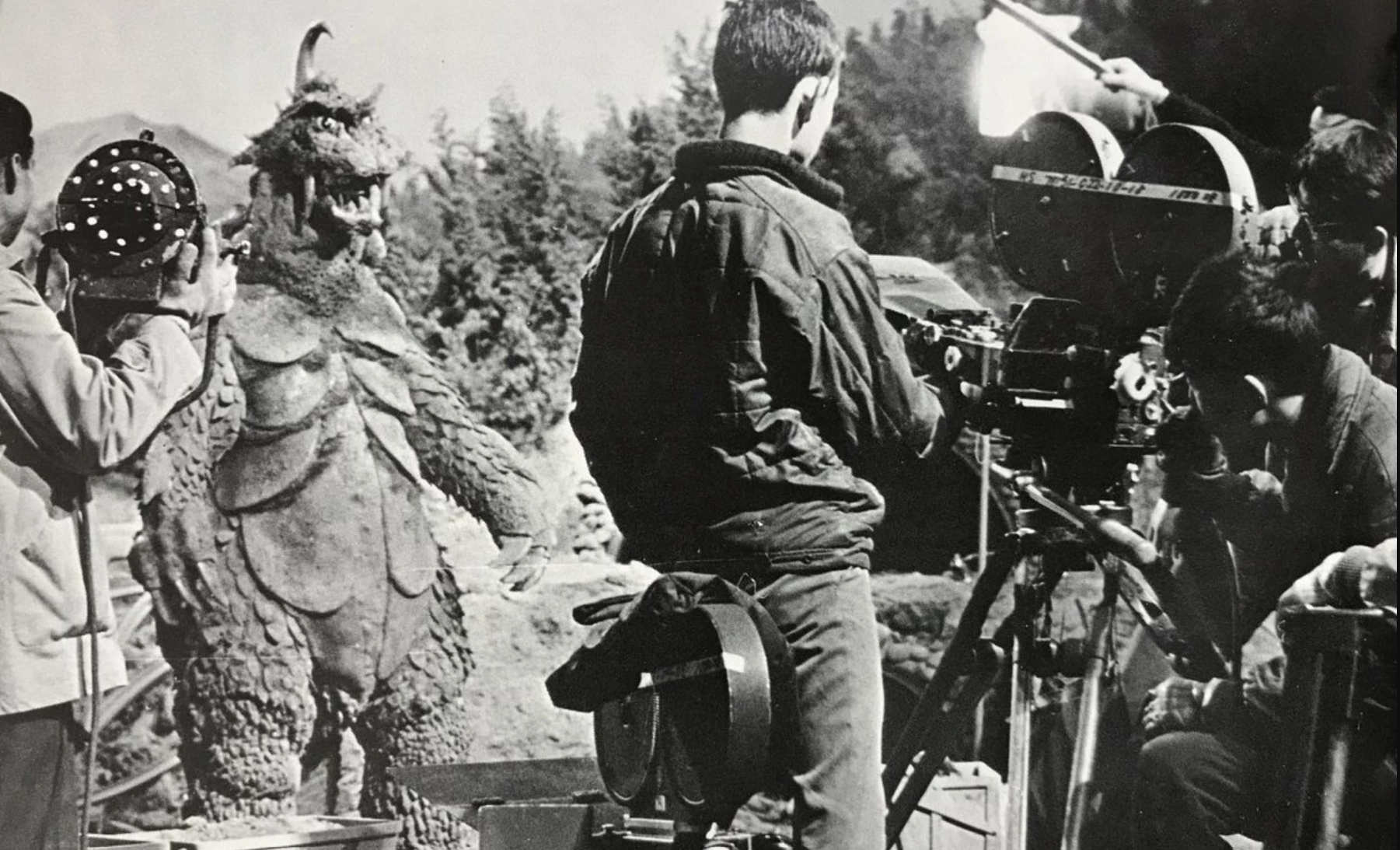

Of great help to Mr. Tsuburaya’s production was his long-standing connection with those running his former creative home base, Toho Studios. This relationship was one of deep respect, with the board of directors even choosing to invest in this new enterprise. Hence, Tsuburaya was also given full access to the warehouse of props and costumes he and his team had made for the Godzilla films. For example, an old Godzilla suit was re-utilized into Gomess, a Manda prop from Atragon (1963) re-appeared later in the show, and the entire Maguma suit from Gorath was used to portray Tolodon, to name a few examples.

Interestingly, producer Toshihiro Iijima himself wrote many episodes under a pen name, most notably the very first to be broadcast, Defeat Gomess! (Episode 2). Also on board for this ultra project was the heir to the Tsuburaya kingdom, Hajime, who would go on to become a regular director for the show alongside the two elders. With the tokusatsu version of the 1992 Olympics Basketball Dream Team in play, production began on this new venture, and Tsuburaya Productions’ first ever entertainment product was well on on its way.

The popularity of Ultra Q galvanized the toku television explosion. Audiences of all ages loved the monster co-stars, or mon-stars that stomped through the show. There were several Godzilla films before 1966, of course, but they had been mostly aimed at adult audiences with their themes of nuclear devastation, moralistic integrity, and the dangers of corruption. This new show, however, was for both adults and children to enjoy together. A family friendly entertainment to be aired on Sunday evenings, and fun primetime viewing before starting another work or school week the following morning.

Once Ultra Q had gone on to become a bona fide ratings success, Tsuburaya decided to revamp his next project, amplify the giant monster quotient, and finally do the first full-fledged Kaiju television show. Longtime Toho screenplay writer Shinichi Sekizawa joined the writing staff to juice up the screenplays, and work quickly began to meet the high demand for more kaiju television.

Several ideas for the follow up show were pitched, but ultimately turned down. The first notable one was WoO (Wū), a Japanese version of popular British television series Doctor Who, in which the titular adventurous space being was a kaijin (“human sized monster”) alien, who would save the day whilst being chased by a government patrol, ala popular American show The Fugitive. The next idea was Bemular (ベムラー Bemurā), then retitled into Scientific Special Search Party: Bemular (科学特捜隊ベムラー Kagaku Tokusō Tai: Bemurā. This pitch would see some of the tropes that would eventually emerge into most Ultra fare, such as a Science Patrol squadron of researchers, with one of its members, the leader of the heroic group of researchers, being able to transform into a giant heroic bird-like being.

The final notable concept was Redman. Evil invading kaiju would be faced by the titular character each week, in a show not too different from the finished product that ultimately wound up on screens. However, for reasons unknown, the design was changed yet again, and the character was renamed into Ultraman. Redman perhaps looked too scary for a family show, as he looked demonic and had horns sprouting from his head. Tsuburaya Productions instead opten for a traditional alien grey look, prominent in science fiction media and supposed alien sightings. It begs question, was this influenced by Ufologist writer George Adamski, who was popular with Japanese readers at the time?

Bemular and Redman were both designed by artist Tohl Narita, who was a contract employee for Tsuburaya, and the designer of many of the ships and monsters seen in Ultra Q. Interestingly, almost all of Narita’s abandoned pitches and concepts were later used in some capacity on Ultraman. The Woo creature became Ultraman’s enemy-of-the-week yeti monster in Episode 30 (Phantom of the Snow Mountains), and Bemular became the very first creature that Ultraman would end up facing in the first episode (Ultra Operation No. 1).

The name Redman was, most notably, turned into the 1972 series of the same name which re-utilized the mothballed concept, re-tooling the alien-fighting, planet-saving character into a much more aggressive character. This clearly strayed from his originally envisioned, heroic, and kid-friendly counterpart. Tsuburaya has since officially released this show for free viewing on video sharing platform YouTube, increasing Redman’s popularity as a cousin show to Ultraman. Redman has even enjoyed a resurrection in comic book form by known kaiju artist Matt Frank, in English, and widely accessible to Western readers.

After production on Ultraman was well underway, promotion began to ramp up, bringing the new hero into the pop consciousness of Japanese television audiences. Thus, a promotional stage spectacle was created to capture the attention of the younger demographic, airing two weeks before the official broadcast debut of ULTRAMAN. This performance would be televised across Japan during primetime; children and adults can tune in and find out the next exciting entertainment up the sleeves of the people behind Ultra Q!

Officially titled The Birth of Ultraman, this production served as the official pilot for the show, known also not only for being Episode 00, but for also being the first-ever entertainment to bear the name “Ultraman”. Helped along by the success of his prior program, Tsuburaya-San directly utilized previous Ultra Q monsters popular with audiences and staged them against the brand-new kaiju coming up, creating a fun call-back, and rivalry; connecting the past to the future. The performance was staged at the Suganami City Hall, and edited into the version which aired on July 10, 1966, at 7PM, originating a trend that is still celebrated to this day, known as Ultraman Day.

The stage show’s story sees Mr. Eiji Tsuburaya entertain the children in attendance with his claims of being able to tame the kaiju, since he’s “The Master of Monsters!”. Each attempt to showcase this ability is interrupted by various comedic shenanigans, such as a team of thieves who are out to steal the kaiju for their own gain, a barbershop quartet singing the Ultraman theme song, and the cast of new kaiju refusing to behave under the command of their “maker”. After a good majority of the monsters escape and begin stirring up conflict amongst themselves, Mr. Tsuburaya calls on the Science Patrol to aide him in taming these rambunctious antics. When the newfound allies arrive to quell the beasts, it is unearthed that this man on the stage is not who he has claimed to be. The real Mr. Tsuburaya would have no issue settling this gargantuan problem.

In a shocking twist, the actual Eiji Tsuburaya is brought onto stage by the Science Patrol, and is revealed to be the true and legitimate “Master of Monsters’. Exhibiting no problem in bringing the wild situation to heel, the fake Mr. Tsuburaya clamors on his knees, begging the man whose identity he just stole to aid him. The Man himself quells the beasts, and peace is restored on stage. Another rendition of the titular and now beloved theme song is performed with the cast all together at curtain call, and the kids are told to “tune in next week at 7pm, to watch the exciting first episode of Ultraman!”

My reaction to this stage production was very positive. This fun, documented history is an absolutely crucial piece to have in any Ultraman fanatic’s library. The play is not in HD, of course, as it’s old broadcast footage, but seeing Eiji Tsuburaya alive and moving in “real life” for the first time was a delightful treat, and alone, well worth the cost of the Mill Creek Blu-ray set of The Birth of Ultraman. Typically, fans are used to the iconic set photos of Eiji Tsuburaya standing very stoically in line with his monster suits for publicity, but this play had him laughing, singing, and telling jokes to entertain the kids attending the show. It is also notable that he was completely self-aware of his role in Japanese popular culture, as the oft cited “master of the monsters’ ‘, even before his death in 1970 and the explosion of Tokusatsu, special effects driven kaiju and superhero media, that permeated after he passed away. Was it all a well-placed publicity event to attract people to his new and exciting product? Perhaps! But it also feels incredibly genuine and shows Mr. Tsuburaya to be a fun guy at heart, and sincerely proud of his latest creation.

Fans in the US should be making a call for more stage productions like this to see official release in North American regions (including any archival footage of the aforementioned cousins which were the Universal Monsters roadshows, and Sid and Marty Krofft live extravaganzas). Now is the best time ever for kaiju and Tokusatsu content on US home video, helping to ensure the preservation of not only the shows themselves, but historic and wonderful events like Ultraman 00 live. There are Kamen Rider, Super Sentai, and even more Ultraman stage productions still being produced to this day in the year 2022. Making these stage shows accessible would prevent a regrettable loss, like that of the infamous Godzilla Vs. Gamera stage play from the 1970s, which has achieved near-mythical status due to its unavailability. Each of these stage productions are notable and should be just as important as any other tie-in merchandise and media.

Every instance of television mentioned above is crucial to the formation of the Ultra Franchise as it is known today, collectively serving as their own unique piece of the puzzle. One should not be discussed without the other. Japan’s Ultra family still graces television and motion picture screens, serving as a beacon of light, bringing joy and happiness to audiences both young and old. With a new iteration and incarnation to the mythos coming nearly every year, audiences in both the series’ native Japan, as well as internationally, are regularly given a pleasant reminder that there will always be heroes to admire and inspire.

After Eiji’s passing, the torch was then picked up and carried by his son Hajime, who had previously directed episodes of his father’s shows. Toshihiro Ijima would remain as a frequent writer, director, and producer on the series until his eventual retirement in 2005.

Ultraman now is inarguably a global franchise, and according to reports from 4Kids around the time of their acquisition of 1996’s Ultraman Tiga, the Ultra franchise has generated $7.4 billion in merchandising revenue from 1966 to 1987 in Japan alone (More than $18 billion adjusted for inflation). What have they generated now, in particular internationally? It must be absolutely astronomical, with this larger-than-life character becoming one of the world’s most recognizable and profitable IP’s, easily standing with Star Wars, Marvel, etc. in the global market.

Here is to the undying legacy of Eiji Tsubaraya, and the burning spirit of those great heroes from the Land of Light!

May the genesis continue!

Sources:

- Eiji Tsuburaya: Master of Monsters – August Ragone (2007, 2014)

San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-6078-9

- The Q Files – Jim Cirronella & Kevin Grays (1996)

Originally published in KAIJU-FAN Issue # 4 November 1996, now on historyvortex.org

- Ultra Q and Ultraman – Wikizilla.com